Thu 30 Sep 2021

Rewinding a 125-year-old clock

Posted by DavidMitchell under Uncategorized

1 Comment

Caveat lectorem: When readers submit comments, they are asked if they want to receive an email alert with a link to new postings on this blog. A number of people have said they do. Thank you. The link is created the moment a posting goes online. Readers who find their way here through that link can see an updated version by simply clicking on the headline above the posting.

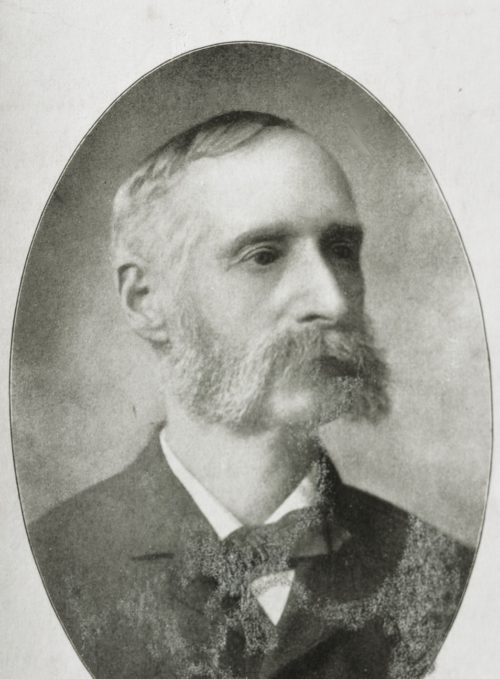

A family heirloom. In 1856, my great-grandfather Luke Parsons moved from Ohio to Kansas, where he went to work as a clerk at the Free State Hotel in Lawrence. Kansas at the time was still a territory, and Congress had decided to let Kansas residents vote on whether to allow slavery when it became a state.

Parsons arrived in Lawrence just in time for two terrorist attacks by pro-slavery “Border Ruffians” from Missouri.

A report by the Kansas Historical Society notes, “The first attack took place on May 21, 1856, when approximately 800 pro-slavery advocates descended upon the Kansas town and proceeded to destroy anti-slavery forces. The second attack, led by William Clark Quantrill on Aug. 21, 1863, resulted in the death of nearly 200 people and the burning of many business and homes within the community.”

“Notably, only a few of the ordinary border ruffians actually owned slaves; most were too poor,” notes Wikipedia. “What motivated them was hatred of Yankees and abolitionists, and fear of free Blacks living nearby.”

The ruffians’ violent attempts to get free staters out of Kansas ahead of the vote was known as “bleeding Kansas.” Abolitionist leader John Brown formed his “army” to protect the abolitionists, and Parsons joined John Brown’s Army. As part of the “Army,” Parsons on Aug.30, 1856, took part in the Battle of Osawatomie, in which members of the opposing militias lost numerous men. Out of such battles, the Civil War (1861-65) erupted.

Parsons (above) did not take part when John Brown’s Army attacked the federal arsenal in Harper’s Ferry, hoping to get weapons to arm slaves for a revolt. It was fortunate Parsons didn’t take part because the attack failed; Brown and other followers were subsequently executed.

During the war itself Parsons led a company of Native American soldiers in the Oklahoma territory as they hunted for “bushwhackers,” who ambushed Union soldiers.

After the war, Parsons took up life on the prairie in Salina, Kansas, where he eventually mail-ordered the clock that inspired this posting.

My father was born in Salina and inherited his grandfather’s clock, which I in turn eventually inherited.

However, the clock long ago stopped working, so in April, I took it to Tim Eriksen, The Clockmaker, in Novato. Eriksen got it working, but within a month its chiming on the hour and half hour stopped. Soon afterward, the hands of the clock stopped turning, so this week I took it back to The Clockmaker.

I was worried how much further repairs would cost, but Eriksen quickly figured out why the bell wasn’t chiming. The spring that drives the striking mechanism needed to be wound more tightly, as did the spring that drives the hands of the clock. Somehow I missed that.

Inside the clock.

Within minutes, Eriksen had the clock working as well as it presumably did 125 years ago, and on the mantel behind our woodstove, it again seems worthy of great-grandfather Parsons.

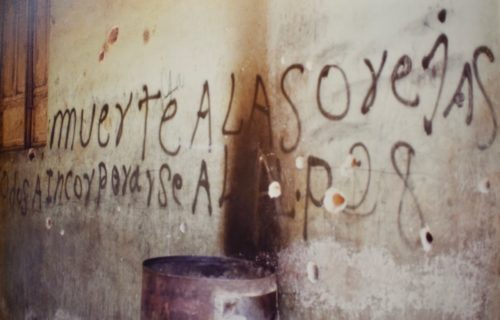

‘Death to the Ears.’ This threatening guerrilla graffiti in San Agustin, El Salvador, was a warning to any would-be government informants. (1982)

‘Death to the Ears.’ This threatening guerrilla graffiti in San Agustin, El Salvador, was a warning to any would-be government informants. (1982)

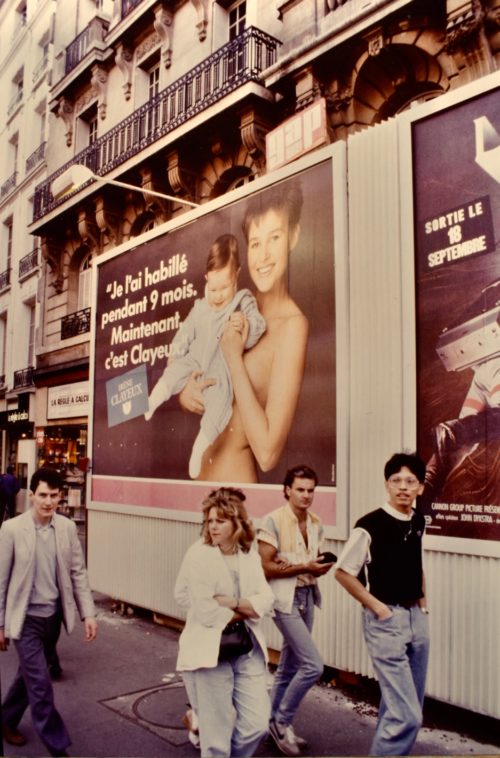

‘I was his home for nine months. Now it’s provided by Clayeux [diapers.]’ A billboard in Paris, 1983.

‘I was his home for nine months. Now it’s provided by Clayeux [diapers.]’ A billboard in Paris, 1983.

Cynthia Clark, serving as my translator, interviews Combatiente William of the Popular Liberation Front at the roadblock. He’s carrying a raw-pineapple snack.

Cynthia Clark, serving as my translator, interviews Combatiente William of the Popular Liberation Front at the roadblock. He’s carrying a raw-pineapple snack.

Inverness’ Chicken Ranch Beach.

Inverness’ Chicken Ranch Beach. Redwoods, Morning. (While the fog is still clearing.)

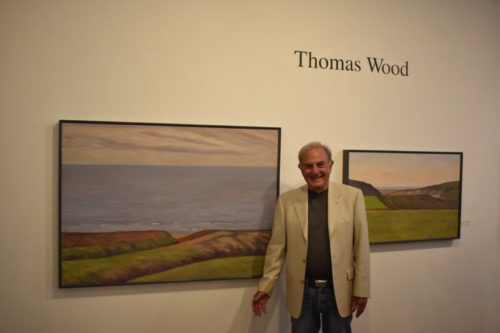

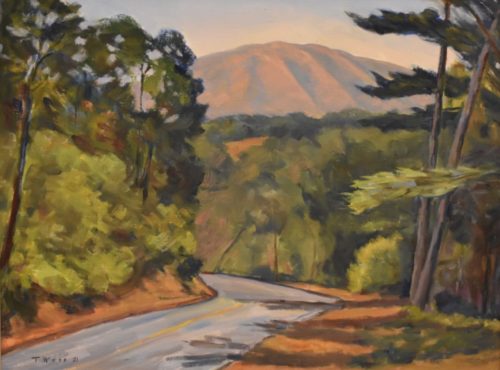

Redwoods, Morning. (While the fog is still clearing.) Black Mountain from Inverness Ridge sold for $1,600. Sales in general were good, and the artist was pleased with the results.

Black Mountain from Inverness Ridge sold for $1,600. Sales in general were good, and the artist was pleased with the results.