Caveat lectorem: When readers submit comments, they are asked if they want to receive an email alert with a link to new postings on this blog. A number of people have said they do. Thank you. The link is created the moment a posting goes online. Readers who find their way here through that link can see an updated version by simply clicking on the headline above the posting.

A family heirloom. In 1856, my great-grandfather Luke Parsons moved from Ohio to Kansas, where he went to work as a clerk at the Free State Hotel in Lawrence. Kansas at the time was still a territory, and Congress had decided to let Kansas residents vote on whether to allow slavery when it became a state.

Parsons arrived in Lawrence just in time for two terrorist attacks by pro-slavery “Border Ruffians” from Missouri.

A report by the Kansas Historical Society notes, “The first attack took place on May 21, 1856, when approximately 800 pro-slavery advocates descended upon the Kansas town and proceeded to destroy anti-slavery forces. The second attack, led by William Clark Quantrill on Aug. 21, 1863, resulted in the death of nearly 200 people and the burning of many business and homes within the community.”

“Notably, only a few of the ordinary border ruffians actually owned slaves; most were too poor,” notes Wikipedia. “What motivated them was hatred of Yankees and abolitionists, and fear of free Blacks living nearby.”

The ruffians’ violent attempts to get free staters out of Kansas ahead of the vote was known as “bleeding Kansas.” Abolitionist leader John Brown formed his “army” to protect the abolitionists, and Parsons joined John Brown’s Army. As part of the “Army,” Parsons on Aug.30, 1856, took part in the Battle of Osawatomie, in which members of the opposing militias lost numerous men. Out of such battles, the Civil War (1861-65) erupted.

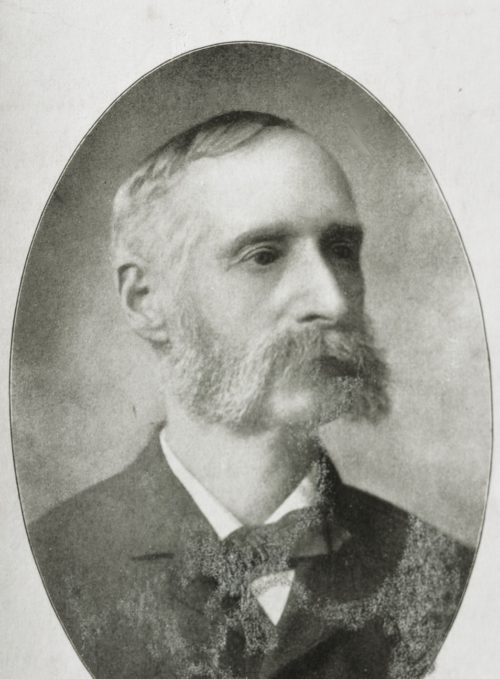

Parsons (above) did not take part when John Brown’s Army attacked the federal arsenal in Harper’s Ferry, hoping to get weapons to arm slaves for a revolt. It was fortunate Parsons didn’t take part because the attack failed; Brown and other followers were subsequently executed.

During the war itself Parsons led a company of Native American soldiers in the Oklahoma territory as they hunted for “bushwhackers,” who ambushed Union soldiers.

After the war, Parsons took up life on the prairie in Salina, Kansas, where he eventually mail-ordered the clock that inspired this posting.

My father was born in Salina and inherited his grandfather’s clock, which I in turn eventually inherited.

However, the clock long ago stopped working, so in April, I took it to Tim Eriksen, The Clockmaker, in Novato. Eriksen got it working, but within a month its chiming on the hour and half hour stopped. Soon afterward, the hands of the clock stopped turning, so this week I took it back to The Clockmaker.

I was worried how much further repairs would cost, but Eriksen quickly figured out why the bell wasn’t chiming. The spring that drives the striking mechanism needed to be wound more tightly, as did the spring that drives the hands of the clock. Somehow I missed that.

Inside the clock.

Within minutes, Eriksen had the clock working as well as it presumably did 125 years ago, and on the mantel behind our woodstove, it again seems worthy of great-grandfather Parsons.

Caveat lectorem: When readers submit comments, they are asked if they want to receive an email alert with a link to new postings on this blog. A number of people have said they do. Thank you. The link is created the moment a posting goes online. Readers who find their way here through that link can see an updated version by simply clicking on the headline above the posting.

A Cal Fire helicopter on Thursday crosses Inverness Ridge to drop water on a containment line for the Woodward Fire in the Point Reyes National Seashore. Smoke from back-burns rises through the forest.

The Woodward Fire, which was started by a lightning strike Aug. 18, was 85 percent contained by this evening after having grown to more than 4,800 acres. Part of the containment has included setting back-burns along Limantour Road. Full containment is expected by Tuesday.

Smoke from the fire has at times made the air in much of West Marin unhealthy, and smoke from hot spots may last for months, the Park Service has warned.

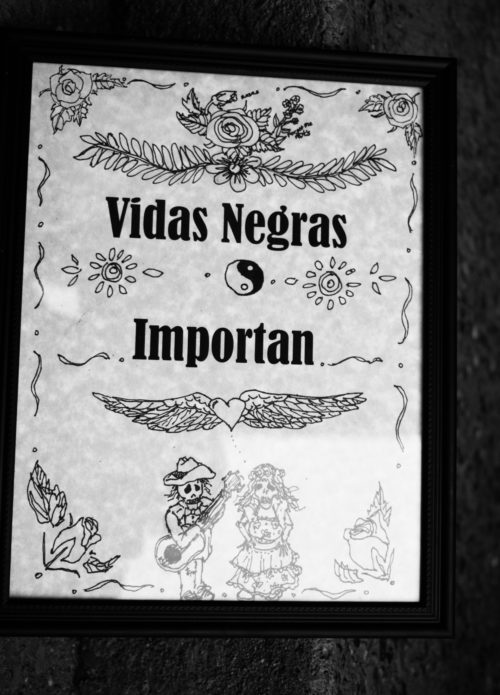

Vidas Negras Importan

The Black Lives Matter movement is sometimes getting overshadowed by the chaos at just a very few of the hundreds of protests around the country. In these isolated cases, looters and vandals have taken advantage of there being crowds in downtown areas. On at least one occasion, however, a covert white supremacist damaged property during a protest to discredit the protesters. Despite all this, only 7 percent of all the protests nationwide have had such problems, The Washington Post reported this past week.

In an effort to refocus public attention on what the movement is really all about stopping the unwarranted killing of Black people by overly aggressive police officers in several cities, I came up with a sign in Spanish. Its intent is to show that criticism of the killings transcends the Black and Anglo Saxon communities.

Maddy Sobel, who often sell jams and jellies in front of the Point Reyes Station post office, is also an artist, and she illustrated one of my signs. Her thought is that if I make some copies of her illustration, she can give them to kids to color with crayons. Sounds good to me. I gave another copy to Toby’s Coffee Bar, and you can see it displayed there without illustration.

Bumping elbows but not shaking hands. From left: Phil Jennings, yours truly, and Gordon Jones

Before the pandemic and sheltering in place, I went to the No Name Bar in Sausalito to listen to live jazz every Friday night. Sunday afternoon, two friends from the No Name dropped by for an outdoor visit. I gave them both copies of the sign, and Jones was so enthusiastic he said he may have it imprinted on t-shirts.

My own family’s efforts to get justice for Black people date from before the Civil War. My great-grandfather Luke Parsons was a member of John Brown’s Army but did not take part in the debacle at Harper’s Ferry. Instead he went on to command a Union Army company of Native Americans fighting in the Oklahoma Territory.

My late father was a Republican who supported the NAACP. I formally joined the movement in the spring of 1968 while I was teaching high school in Leesburg, Florida. At the time, Willis V. McCall was the sheriff of Lake County, Florida, where Leesburg is located. He had come to be called the worst sheriff in the US and in private bragged he’d “killed more n-ggers” than any other man.

When McCall came up for reelection in 1968, a well-regarded Leesburg police officer ran against him, and I signed up to canvass voters in Black neighborhoods for the challenger. Unfortunately, McCall again won but was defeated four years later after yet another cruelty: a mentally impaired Black man was kicked to death in the Lake County jail.

Civil rights activist Julian Bond (center) in 1970 with members of an Upper Iowa University group, the Brotherhood, who had invited him to speak on campus. While he was studying at Morehouse College in the early 1960s, Bond had established the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a.k.a. SNCC (pronounced “Snick”).

In the fall of 1968 I began teaching English and journalism at Upper Iowa University and the next semester became a faculty advisor to the new Black student union. As the group explained in a flyer: “The Brotherhood was founded and chartered in February 1969. It is an organized group open to anyone interested in furthering their knowledge of Black culture…

“Under the able leadership of our past president, Rick Weber, and the helpful assistance of our advisors, Mr. Mitchell and Mr. [Robert] Schenck, the Brotherhood has enriched campus life by promoting various social functions, such as the annual Black Night.” Besides that variety show, the Brotherhood has sponsored “an inter-racial forum, and a play, A Raisin in the Sun. Our biggest accomplishment was, of course, acquisition of a Black Cultural House.”

Half a century later, I still recall advising the Brotherhood as one of my most informative experiences.