Entries tagged with “El Salvador”.

Did you find what you wanted?

Sat 29 Jan 2022

Caveat lectorem: When readers submit comments, they are asked if they want to receive an email alert with a link to new postings on this blog. A number of people have said they do. Thank you. The link is created the moment a posting goes online. Readers who find their way here through that link can see an updated version by simply clicking on the headline above the posting.

This weekend I rediscovered a trove of old t-shirts when a knob came loose on a dresser drawer in the bedroom. The drawer, which I had rarely opened, turned out to be full of badly worn shirts I’d collected during the past four decades but then forgotten about. In picking through them, I found many of these t-shirts were souvenirs of places I’d been and things I’d observed. T-shirts are often sold as such, but what I discovered is they can be arranged to tell stories.

This Synanon t-shirt, which an ex-member of the cult gave me, was an instant reminder of the late 1970s when I edited and published The Point Reyes Light and when Synanon was headquartered in Marshall. As The Light revealed, Synanon’s focus had evolved from drug-treatment to making money. It claimed to be a church in order to avoid regulations, as well as taxes on that money. Its lawyers began referring to Synanon as a “cult.” From there it was a short step into becoming a criminally violent organization. This history makes the shirt’s “Synanon the People Business” message all the more ironic.

Now here’s a souvenir I can use some help with. The shirt commemorates “The First Annual West Marin Oyster Festival.” I vaguely remember such an event, but I don’t recall where it was held nor whether there were more West Marin Oyster Festivals. Any reader who does remember is encouraged to let us all know know in the comment section.

“It Was Another Safe & Sane 4th in Bolinas.” What year was this? What prompted the boast?

How about this t-shirt from  the Gibson House, once a highly regarded bar and restaurant in Bolinas? Was there a particular issue that inspired this? If so, when?

The Marshall Tavern had its own shirt. Does anyone remember when this came out?

The Point Reyes Light distributed a number of t-shirts. This one from the 1970s is a reminder of the days when the cover price was a tenth of what it is today.

One of The Light’s particularly popular features was Tomales cartoonist Kathryn LeMieux’s Feral West. As seen, there was a time that graffiti artists frequently scrawled “SKIDS” along West Marin roadsides.

The vast majority of Mexican immigrants in West Marin are from Jalostotitlán. Beginning in the 1980s, The Light sent reporters to southern Mexico three times to document the historic immigration from Jalos.

As for my own foreign reporting, in the early 1980s, I took a two-year leave from The Light to report for The San Francisco Examiner. The then-Hearst-owned daily sent me to Central America for three months to cover fighting underway in El Salvador and Guatemala.

Surprising acronym. One of my favorite t-shirts from these adventures was from the SPCA Salvadoran Press Corps Association.

Because unfamiliar people showing up during a firefight can easily be suspected of being enemy personnel, the back of my SPCA shirt carried the message: !PERIODISTA! !No DISPARE! Journalist! Don’t shoot!

An example of the violence in the air when I was in Central America. However, since “your country” referred to El Salvador, why was the message in English and not Spanish?

Sun 19 Sep 2021

Posted by DavidMitchell under Uncategorized

1 Comment

My father was a good photographer, and when he travelled, he was constantly shooting pictures of the landscape. I, in turn, got in the habit of photographing the signs I saw along the way since many of them represent different communities and values. I started doing this back in the 1970s and 80s. This posting is a representative sampling from that era.

The line is catchy, but ‘My shirt for a beer!’ didn’t seem to catch the attention of this housemaid lugging food to work in Paris, circa 1976.

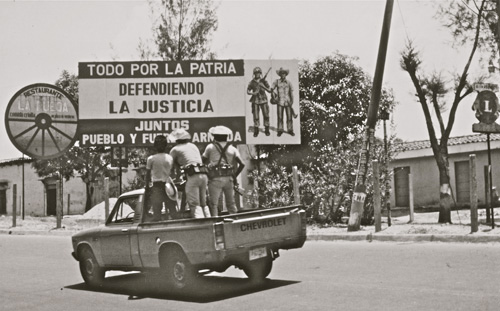

‘All for the Country Defending Justice, the Junta, the People, & Armed Forces.’ A 1982 billboard in San Salvador, El Salvador, supported the government in its battle against an insurgency led by leftist guerrillas.

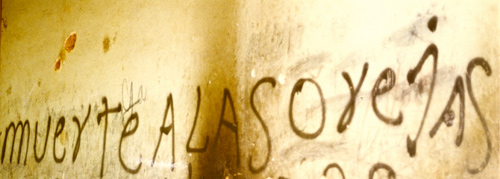

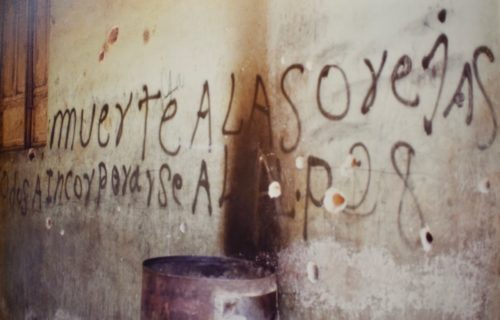

‘Death to the Ears.’ This threatening guerrilla graffiti in San Agustin, El Salvador, was a warning to any would-be government informants. (1982)

‘Death to the Ears.’ This threatening guerrilla graffiti in San Agustin, El Salvador, was a warning to any would-be government informants. (1982)

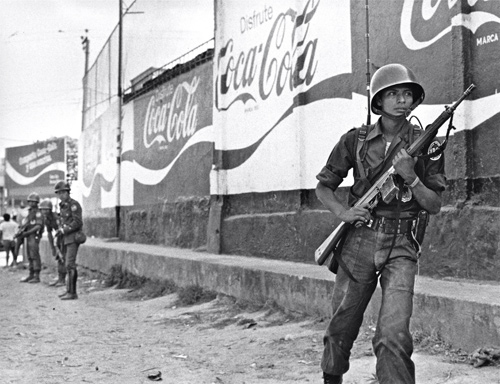

San Salvador’s election center with its large Coca Cola ads received military protection after it came under fire one morning in 1982.

‘With the murder of Ana Maria, the Salvadoran revolution will not stop.’ This declaration strung across a rural highway let travelers know they were entering guerrilla-held territory.

Paris, 1983.

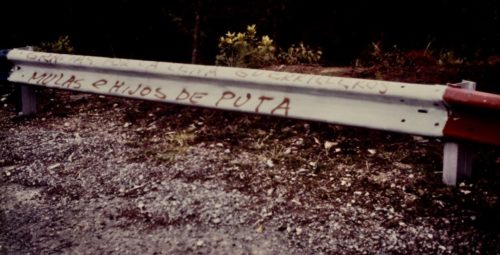

In 1982 guerrillas blocked a Salvadoran highway by felling trees across it. Because the government had previously barred local residents from cutting timber in the area, the locals put up a sarcastic sign of appreciation: ‘Thanks for the firewood, guerrillas, mules and sons of a whore.’

Guatemala. The country’s military strongman, Gen. Lucas Garcia, in 1981 took advantage of his position to have a large sign put up along a new highway, giving him credit for it: ‘Another public work by the government of General Lucas.’

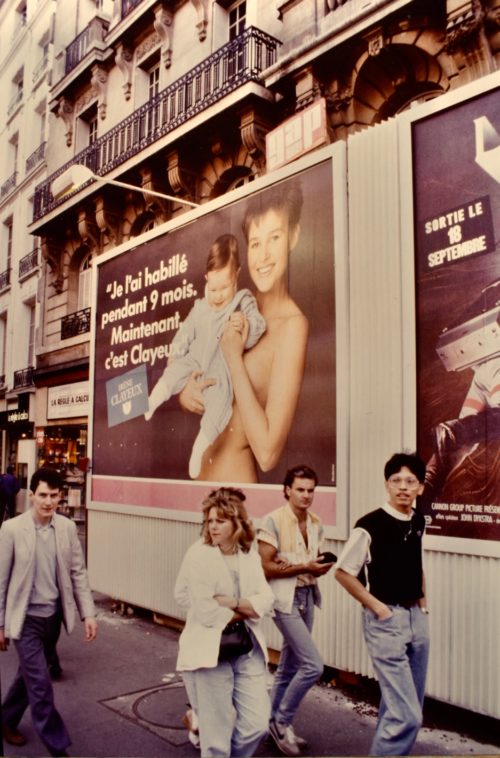

‘I was his home for nine months. Now it’s provided by Clayeux [diapers.]’ A billboard in Paris, 1983.

‘I was his home for nine months. Now it’s provided by Clayeux [diapers.]’ A billboard in Paris, 1983.

Sat 11 Sep 2021

Posted by DavidMitchell under Uncategorized

1 Comment

Caveat lectorem: When readers submit comments, they are asked if they want to receive an email alert with a link to new postings on this blog. A number of people have said they do. Thank you. The link is created the moment a posting goes online. Readers who find their way here through that link can see an updated version by simply clicking on the headline above the posting.

The Panjshir Valley had been the one province of Afghanistan the Taliban had not conquered until last week. When it was conquered, provincial commanders blamed their loss on Pakistani aid to the Taliban. Many residents of the valley are Tajiks, as are many residents of neighboring Iran. As a result, the loss upset Iran, along with Pakistan’s traditional adversary, India.

Craziness. But that seems typical of warfare. As a reporter for The San Francisco Examiner, I first observed combat craziness during El Salvador’s civil war 38 years ago. I was startled by it. As it happened, I told my story to a reporter from The Des Moines Register, which soon put it in print:

Harrowing experiences in war-torn El Salvador

By Jerry Perkins, Register Staff Writer

(Photos by Dave Mitchell added)

SAN SALVADOR, EL SALVADOR. We went looking for guerrillas; instead we found the war. Photographer Rich Rickman and I left the capital city early one morning by taxi and headed east on the Littoral Highway. Our taxi driver, Jose Alvorado, carefully instructed us that we were not to tell the army where we were headed, a small village named San Augustin (45 minutes southeast of the capital) where the guerrillas often come to buy supplies….

_________________________________

A Salvadoran peasant family in whose front yard guerrillas bombed a utility pole. The railroad sign says, “Stop, Look, and Listen.”

____________________________

As we drove up the highway, Salvadoran troops were walking toward the river and came up to the taxi to beg for water. One was carrying a limp iguana, a bullet hole in its head. ‘There’s a war going on, and these guys are wasting ammunition on iguanas,’ I said to Rickman.

Up ahead , we could see the taxicab hired by David Mitchell of the San Francisco Examiner and Cynthia Clark, his translator. Mitchell and Clark, standing beside a tree, were taking pictures of a Salvadoran soldier, his shirt unbuttoned to the waist, his M-16 blazing away. I thought the guy was just showing off for Clark. Another waste of ammo.

But as we drove closer, the leaves in the tree above the group started to disintegrate. Then Mitchell and Clark jumped behind the tree and crouched for cover.

Salvadoran soldiers take cover in the firefight with guerrillas from the Popular Liberation Front.

The reporter in me took over. I was frozen in the front seat, my eyes glued to the tree and the people behind it. ‘Oh my God,’ I remember thinking. ‘I’m watching those people get shot!’ Then Rickman called my name, ‘Jerry,’ he said, ‘get out of the *$@# cab.’ I looked around. Rickman was lying in the ditch. Alvarado, the taxi driver, was beside him. I scrambled out and crouched beside the cab. Mitchell and Clark, who weren’t touched by the shooting, ran to their cab and headed back to the village by the river. We got back in our cab and prepared to return with them….

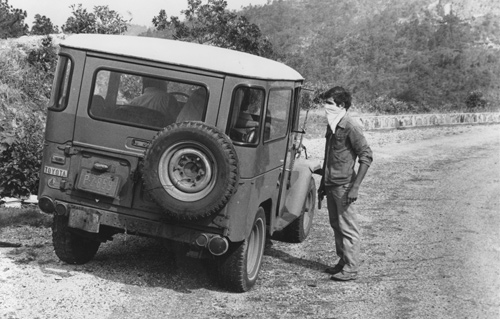

A Salvadoran guerrilla stops a Toyota jeep belonging to the government-owned phone company. And then lets it pass.

Mitchell, a lanky, gregarious Californian, came up with the best story of the trip. He was taking pictures of guerrillas checking cars at a roadblock when a Toyota jeep was stopped. Mitchell thought the jeep looked like it belonged to ANTEL, the Salvadoran national phone company.

Cynthia Clark, serving as my translator, interviews Combatiente William of the Popular Liberation Front at the roadblock. He’s carrying a raw-pineapple snack.

Cynthia Clark, serving as my translator, interviews Combatiente William of the Popular Liberation Front at the roadblock. He’s carrying a raw-pineapple snack.

Mitchell learned that the guerrillas let telephone company employees clear the roadblocks so they can keep the phone lines open in guerrilla-held territory. In return the company lets the guerrillas use the jeep at night for road patrols. The guerrillas return the jeep every morning. It’s that kind of war. Friday, July 1, 1983 The Des Moines Register

_____________________________

For government employees in time of war to loan vehicles to the enemy would seem to epitomize craziness. But so do the Taliban’s hostile relations with India and Iran. If my country were going to war in that part of the world, I’d want those two on my side.

Tags: Cynthia Clark, Des Moines Register, El Salvador, guerrillas, Iran, Jerry Perkins, Pakistan, Panjshir Valley, Popular Liberation Front, San Francisco Examiner, Taliban

Fri 15 Aug 2014

Posted by DavidMitchell under History, Photography

1 Comment

This week’s posting looks at some of the signs of life I’ve photographed over the years. Why signs? My premise is that what gets displayed in public is a good indication of the social-cultural concerns of a certain time and place.

Left Bank, Paris, 1985

The now-defunct newspaper France Soir once had one of the largest circulations in Europe, approximately 1.5 million. Parisians are known for their sophistication, so the gaudiness of the newspaper’s self-promotion seemed a bit gauche: “the BIG BINGO! with France Soir, 250,000,000 to Win.”

Paris, 1985

This scene also stuck me as a bit incongruous. A houseworker wearily lugs home food for dinner while a semi-topless girl on a billboard behind her flirtatiously laughs, “My shirt for a beer.”

A city cemetery in northeastern Iowa, 1969

A sudden, unexplained shudder or shivering, according to some superstition, can be caused by someone walking over your future grave. Nonetheless, I figured it was highly unlikely my ghost-like shadow was giving some far-off person a creepy feeling so I took my time to compose an image.

San Salvador, 1982

With FMLN (Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front) guerrillas mounting an insurrection, armed soldiers and bodyguards were seen throughout El Salvador’s capital during the weeks before the 1982 general election. The political billboard these men are passing says: “All for the Homeland, Defending Justice, Together the People and the Armed Forces.”

Note the Lions Club sign at the right.

San Agustín, El Salvador, 1982.

Control over San Agustín in eastern El Salvador went back and forth between the government and leftist guerrillas for months. On this wall pockmarked with bullet holes, guerrilla graffiti warned, “Death to the Ears,” the ears being townspeople who were government informants.

San Salvador, 1982

Coming upon a patrol of Salvadoran soldiers in pursuit of a guerrilla sniper outside a Coca-Cola bottling plant, I couldn’t help but remember the 1971 Coca-Cola commercial: “I’d like to teach the world to sing in perfect harmony. I’d like to buy the world a Coke and keep it company.” Fat chance.

Alas, even though the insurrection has ended, El Salvador is still wracked with criminal violence.

San Salvador, 1982

This election center had been under fire from guerrillas earlier in the day, and the office was under heavily armed protection. With a national election only weeks away, the official slogan was: “Your vote: the solution.”

The election resulted in a rightwing demagogue, Roberto D’Aubuisson of the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA party), becoming head of the Constituent Assembly (the national legislature). More significantly, days of political negotiations ultimately led to a moderate, US-educated economist, Álvaro Magaña, becoming head of state.

As time has passed, the former guerrillas of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front have gained legitimacy as a political party, and on March 12, Salvador Sánchez-Terán, FMLN’s candidate, won the presidential election in a runoff.

Before I sign off, I should note there are many collections of public-sign photography, each different because of time and place and because of each photographer’s unique framing of the world he sees. If you get a chance, pick up a copy of Neon Nevada by newsman Peter Laufer and his wife Sheila Swan Laufer. It’s fascinating in style and concept (and available online).

Sun 11 May 2014

Posted by DavidMitchell under Photography

Comments Off on A few of my photos in war and peace from West Marin to Southeast Asia to Central America

“Every picture tells a story, don’t it?” Rod Stewart

Cows heading toward the milking barn at Steve and Sharon Doughty’s ranch in Point Reyes Station. Of all the photos I’ve shot of West Marin agriculture, this is my favorite (2004).

The newsroom of The Point Reyes Light when the newspaper was located in Point Reyes Station’s Old Creamery Building (2004).

One day I heard something banging around in the firebox of the newsroom’s potbellied stove, which was not lit, so I opened the door to look inside. This house finch, which had apparently fallen down the chimney, flew out and started flying around the room, banging into the closed skylights.

I opened a skylight, but the finch didn’t fly out. Instead it landed on the antenna to our weather radio and perched there looking out over the world. The scene seemed so symbolic he could have been an avian journalist.

Before long a house finch outside the building began singing. The one inside sang back. After several seconds of their calling back and forth, the finch in the newsroom finally flew out the open skylight.

A Golden-crowned sparrow disguised as a stained-glass window, Point Reyes Station (2004).

Scotty’s Castle in Death Valley (2005).

The castle was built in the 1920s by Albert Mussey Johnson, a millionaire from Chicago. Scotty (Walter Scott) was a con man, who took advantage of Johnson, as well as others. Nonetheless, Johnson kept Scotty around to entertain guests with his storytelling.

Thailand (1986).

Two mothers and their children in one of Thailand’s semi-isolated hilltribes.

A Thai hilltribe father and his son (1986).

The father is holding a Point Reyes Light ballpoint pen, which I had given him. The pens were made in 1979 to commemorate the paper’s winning the Pulitzer Prize for Meritorious Public Service.

Thailand’s hilltribes grow opium poppies, as well as bananas and other crops. Here a man in his hut without windows, only gaps between wall boards for light, smokes opium in a pipe (1986).

Rangoon, Burma (1986).

Two Buddhists pray outside the Shwedagon Pagoda. In 1989, the military government changed the country’s name to Myanmar because Burma was the name the British used when the country was their colony. Some citizens, however, question the military’s right to change their country’s name, and many continue to use the name Burma. The name comes from the name of the country’s largest ethnic group, the Bamar.

Mandalay, Burma (1986).

Buddhist monks in Thailand and Burma are considered novices before they turn 20. Most live monastic lives for only short periods, a few years or even just a few days. Youths receive schooling inside or outside of their temple. Helping take care of the temple is one of their main responsibilities. Novices are not expected to be continually solemn, and these boys felt free to roughhouse with each other.

Boy tending water buffalo at the edge of the Irrawaddy River at Mandalay (1986).

Guatemala (1982).

Two Mayan girls wash dishes at a pila (outdoor trough) because their homes on a finca (plantation) lack running water. For many women in rural villages, washing dishes and clothes together at a community pila is their primary time to socialize.

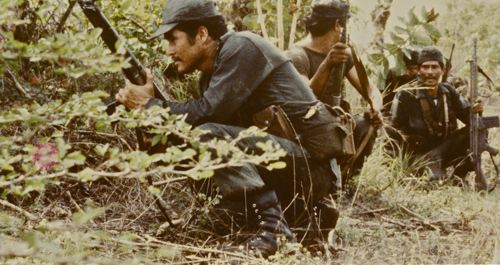

El Salvador (1983).

Government forces take cover during a firefight with FMLN guerrillas. The government patrol, which had been fighting all night, was exhausted and retreating under fire.

Guerrilla-held territory, El Gramal, El Salvador (1983).

A guerrilla stops a vehicle belonging to Antel, the government-owned phone company, and then sends it on its way. Earlier in the day, an Antel driver divulged a bizarre arrangement whereby the guerrillas regularly borrowed the four-wheel-drive Toyota for night patrols but returned it to Antel in the morning. Such cooperation probably explained why an Antel manager in El Gramal said the government phone company in his area was able to operate as usual even though Popular Liberation Front guerrillas had by then occupied the region for six months.

Tags: Albert Mussey Johnson, Antel, Buddhism, Burma, Death Valley, Doughty ranch, El Salvador, finca, Golden-crowned sparrow, Guatemala, House finch, Irrawaddy River, Mandalay, Myanmar, opium, pila, Point Reyes Light, Rangoon, Scotty's Castle, Shwedagon Pagoda, Thailand

‘Death to the Ears.’ This threatening guerrilla graffiti in San Agustin, El Salvador, was a warning to any would-be government informants. (1982)

‘Death to the Ears.’ This threatening guerrilla graffiti in San Agustin, El Salvador, was a warning to any would-be government informants. (1982)

‘I was his home for nine months. Now it’s provided by Clayeux [diapers.]’ A billboard in Paris, 1983.

‘I was his home for nine months. Now it’s provided by Clayeux [diapers.]’ A billboard in Paris, 1983.

Cynthia Clark, serving as my translator, interviews Combatiente William of the Popular Liberation Front at the roadblock. He’s carrying a raw-pineapple snack.

Cynthia Clark, serving as my translator, interviews Combatiente William of the Popular Liberation Front at the roadblock. He’s carrying a raw-pineapple snack.