Entries tagged with “Guatemala”.

Did you find what you wanted?

Sat 29 Jan 2022

Caveat lectorem: When readers submit comments, they are asked if they want to receive an email alert with a link to new postings on this blog. A number of people have said they do. Thank you. The link is created the moment a posting goes online. Readers who find their way here through that link can see an updated version by simply clicking on the headline above the posting.

This weekend I rediscovered a trove of old t-shirts when a knob came loose on a dresser drawer in the bedroom. The drawer, which I had rarely opened, turned out to be full of badly worn shirts I’d collected during the past four decades but then forgotten about. In picking through them, I found many of these t-shirts were souvenirs of places I’d been and things I’d observed. T-shirts are often sold as such, but what I discovered is they can be arranged to tell stories.

This Synanon t-shirt, which an ex-member of the cult gave me, was an instant reminder of the late 1970s when I edited and published The Point Reyes Light and when Synanon was headquartered in Marshall. As The Light revealed, Synanon’s focus had evolved from drug-treatment to making money. It claimed to be a church in order to avoid regulations, as well as taxes on that money. Its lawyers began referring to Synanon as a “cult.” From there it was a short step into becoming a criminally violent organization. This history makes the shirt’s “Synanon the People Business” message all the more ironic.

Now here’s a souvenir I can use some help with. The shirt commemorates “The First Annual West Marin Oyster Festival.” I vaguely remember such an event, but I don’t recall where it was held nor whether there were more West Marin Oyster Festivals. Any reader who does remember is encouraged to let us all know know in the comment section.

“It Was Another Safe & Sane 4th in Bolinas.” What year was this? What prompted the boast?

How about this t-shirt from  the Gibson House, once a highly regarded bar and restaurant in Bolinas? Was there a particular issue that inspired this? If so, when?

The Marshall Tavern had its own shirt. Does anyone remember when this came out?

The Point Reyes Light distributed a number of t-shirts. This one from the 1970s is a reminder of the days when the cover price was a tenth of what it is today.

One of The Light’s particularly popular features was Tomales cartoonist Kathryn LeMieux’s Feral West. As seen, there was a time that graffiti artists frequently scrawled “SKIDS” along West Marin roadsides.

The vast majority of Mexican immigrants in West Marin are from Jalostotitlán. Beginning in the 1980s, The Light sent reporters to southern Mexico three times to document the historic immigration from Jalos.

As for my own foreign reporting, in the early 1980s, I took a two-year leave from The Light to report for The San Francisco Examiner. The then-Hearst-owned daily sent me to Central America for three months to cover fighting underway in El Salvador and Guatemala.

Surprising acronym. One of my favorite t-shirts from these adventures was from the SPCA Salvadoran Press Corps Association.

Because unfamiliar people showing up during a firefight can easily be suspected of being enemy personnel, the back of my SPCA shirt carried the message: !PERIODISTA! !No DISPARE! Journalist! Don’t shoot!

An example of the violence in the air when I was in Central America. However, since “your country” referred to El Salvador, why was the message in English and not Spanish?

Sun 19 Sep 2021

Posted by DavidMitchell under Uncategorized

1 Comment

My father was a good photographer, and when he travelled, he was constantly shooting pictures of the landscape. I, in turn, got in the habit of photographing the signs I saw along the way since many of them represent different communities and values. I started doing this back in the 1970s and 80s. This posting is a representative sampling from that era.

The line is catchy, but ‘My shirt for a beer!’ didn’t seem to catch the attention of this housemaid lugging food to work in Paris, circa 1976.

‘All for the Country Defending Justice, the Junta, the People, & Armed Forces.’ A 1982 billboard in San Salvador, El Salvador, supported the government in its battle against an insurgency led by leftist guerrillas.

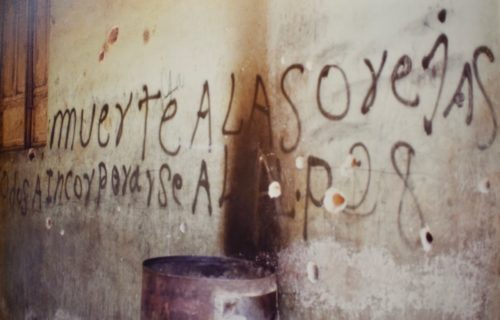

‘Death to the Ears.’ This threatening guerrilla graffiti in San Agustin, El Salvador, was a warning to any would-be government informants. (1982)

‘Death to the Ears.’ This threatening guerrilla graffiti in San Agustin, El Salvador, was a warning to any would-be government informants. (1982)

San Salvador’s election center with its large Coca Cola ads received military protection after it came under fire one morning in 1982.

‘With the murder of Ana Maria, the Salvadoran revolution will not stop.’ This declaration strung across a rural highway let travelers know they were entering guerrilla-held territory.

Paris, 1983.

In 1982 guerrillas blocked a Salvadoran highway by felling trees across it. Because the government had previously barred local residents from cutting timber in the area, the locals put up a sarcastic sign of appreciation: ‘Thanks for the firewood, guerrillas, mules and sons of a whore.’

Guatemala. The country’s military strongman, Gen. Lucas Garcia, in 1981 took advantage of his position to have a large sign put up along a new highway, giving him credit for it: ‘Another public work by the government of General Lucas.’

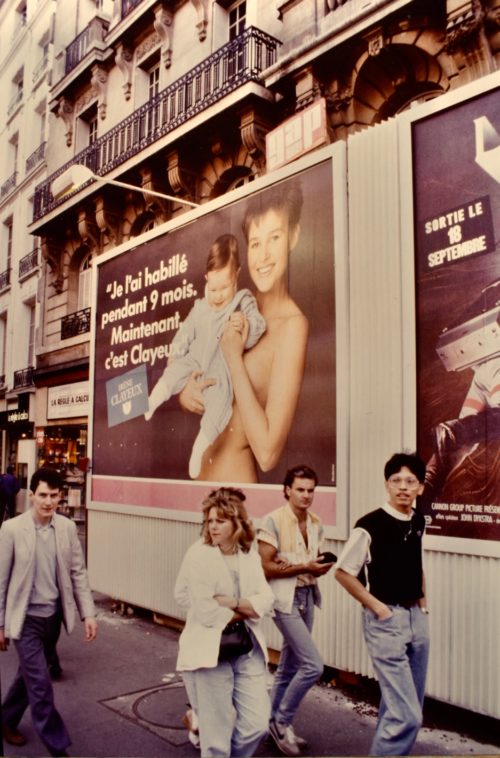

‘I was his home for nine months. Now it’s provided by Clayeux [diapers.]’ A billboard in Paris, 1983.

‘I was his home for nine months. Now it’s provided by Clayeux [diapers.]’ A billboard in Paris, 1983.

Sun 11 May 2014

Posted by DavidMitchell under Photography

Comments Off on A few of my photos in war and peace from West Marin to Southeast Asia to Central America

“Every picture tells a story, don’t it?” Rod Stewart

Cows heading toward the milking barn at Steve and Sharon Doughty’s ranch in Point Reyes Station. Of all the photos I’ve shot of West Marin agriculture, this is my favorite (2004).

The newsroom of The Point Reyes Light when the newspaper was located in Point Reyes Station’s Old Creamery Building (2004).

One day I heard something banging around in the firebox of the newsroom’s potbellied stove, which was not lit, so I opened the door to look inside. This house finch, which had apparently fallen down the chimney, flew out and started flying around the room, banging into the closed skylights.

I opened a skylight, but the finch didn’t fly out. Instead it landed on the antenna to our weather radio and perched there looking out over the world. The scene seemed so symbolic he could have been an avian journalist.

Before long a house finch outside the building began singing. The one inside sang back. After several seconds of their calling back and forth, the finch in the newsroom finally flew out the open skylight.

A Golden-crowned sparrow disguised as a stained-glass window, Point Reyes Station (2004).

Scotty’s Castle in Death Valley (2005).

The castle was built in the 1920s by Albert Mussey Johnson, a millionaire from Chicago. Scotty (Walter Scott) was a con man, who took advantage of Johnson, as well as others. Nonetheless, Johnson kept Scotty around to entertain guests with his storytelling.

Thailand (1986).

Two mothers and their children in one of Thailand’s semi-isolated hilltribes.

A Thai hilltribe father and his son (1986).

The father is holding a Point Reyes Light ballpoint pen, which I had given him. The pens were made in 1979 to commemorate the paper’s winning the Pulitzer Prize for Meritorious Public Service.

Thailand’s hilltribes grow opium poppies, as well as bananas and other crops. Here a man in his hut without windows, only gaps between wall boards for light, smokes opium in a pipe (1986).

Rangoon, Burma (1986).

Two Buddhists pray outside the Shwedagon Pagoda. In 1989, the military government changed the country’s name to Myanmar because Burma was the name the British used when the country was their colony. Some citizens, however, question the military’s right to change their country’s name, and many continue to use the name Burma. The name comes from the name of the country’s largest ethnic group, the Bamar.

Mandalay, Burma (1986).

Buddhist monks in Thailand and Burma are considered novices before they turn 20. Most live monastic lives for only short periods, a few years or even just a few days. Youths receive schooling inside or outside of their temple. Helping take care of the temple is one of their main responsibilities. Novices are not expected to be continually solemn, and these boys felt free to roughhouse with each other.

Boy tending water buffalo at the edge of the Irrawaddy River at Mandalay (1986).

Guatemala (1982).

Two Mayan girls wash dishes at a pila (outdoor trough) because their homes on a finca (plantation) lack running water. For many women in rural villages, washing dishes and clothes together at a community pila is their primary time to socialize.

El Salvador (1983).

Government forces take cover during a firefight with FMLN guerrillas. The government patrol, which had been fighting all night, was exhausted and retreating under fire.

Guerrilla-held territory, El Gramal, El Salvador (1983).

A guerrilla stops a vehicle belonging to Antel, the government-owned phone company, and then sends it on its way. Earlier in the day, an Antel driver divulged a bizarre arrangement whereby the guerrillas regularly borrowed the four-wheel-drive Toyota for night patrols but returned it to Antel in the morning. Such cooperation probably explained why an Antel manager in El Gramal said the government phone company in his area was able to operate as usual even though Popular Liberation Front guerrillas had by then occupied the region for six months.

Tags: Albert Mussey Johnson, Antel, Buddhism, Burma, Death Valley, Doughty ranch, El Salvador, finca, Golden-crowned sparrow, Guatemala, House finch, Irrawaddy River, Mandalay, Myanmar, opium, pila, Point Reyes Light, Rangoon, Scotty's Castle, Shwedagon Pagoda, Thailand

Tue 21 May 2013

Posted by DavidMitchell under General News, History

1 Comment

When a Guatemalan court on May 10 found former Guatemalan dictator Efraín Ríos Montt guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity while head of state, I like many indigenous Guatemalans was pleased. Officials in that Central American country had for decades committed atrocities with impunity.

The case has special interest for me because my stepdaughters are from Guatemala and because 30 years ago I reported on and photographed some of the Guatemalan civil war for the old San Francisco Examiner.

General Efraín Ríos Montt, who became president of Guatemala in a March 1982 coup, was kicked out of office in an August 1983 coup. (AP photo by Moises Castillo)

Unfortunately, the good news was not to last. Impunity again raised its ugly head. On Monday, the Guatemalan Constitutional Court overturned the conviction because of a dispute over which lower court judges should have heard the case. Now the trial will have to return to where it stood on April 19, once the dispute over the judges is resolved.

General Ríos Montt had been clearly elected president in 1974, but blatant election fraud prevented him from taking office. Quixotically, he then fled to California and joined the Eureka-based Gospel Outreach fundamentalist movement.

After returning to Guatemala, Ríos Montt, along with two other military men seized power in a mostly bloodless coup in 1982 and formed a three-man junta. Less than three months after the coup, however, Ríios Mott dissolved the junta and became dictator.

Helping orchestrate the coup, according to the US liberal group Democratic Underground, were “gringo evangelical cronies [who were] co-founders of the Church of the Word, a Guatemala-based offshoot of Gospel Outreach.”

(Gringo, by the way, is slang but not derogatory. In Spain, the word has been around for more than two centuries. Initially, it was simply a way of referring to people from other places whose speech was difficult to understand. Gringo, in fact, is a variant of griego meaning “Greek,” as in it’s Greek to me.)

Estancia de la Virgen. A refugee stands in front of his former home, which was destroyed by the Guatemalan Army on March 31, 1982.

Well before Ríos Montt took power, the army had begun massacring indigenous villagers lest leftist guerrillas get food or recruits from them. A story I wrote for The Examiner made public for the first time that Guatemalan soldiers had massacred 180 residents of two Indian villages, Trinitaria and El Quetzal, near the Mexican border in February 1982.

In the destruction of Estancia de la Virgen, which occurred after Ríos Montt had taken power, the army ordered all the villagers to relocate to the less-remote village of San Antonio las Trojes where it could keep an eye on them.

In the destruction of Estancia de la Virgen, which occurred after Ríos Montt had taken power, the army ordered all the villagers to relocate to the less-remote village of San Antonio las Trojes where it could keep an eye on them.

Soldiers use the belfry of the San Antonio las Trojes cathedral as a guard tower.

The army had attacked the village of 1,800 previously, killing many residents including children who were beheaded with machetes. This time all but eight men fled, and soldiers shot them to death.

“The men had stayed in their houses, believing God would protect them,” a guide named Miguel told me. There was no road to Estancia de la Virgen, and getting there required hiring three refugees from the village to guide my translator and me through the steep terrain.

A soldier in San Antonio las Trojes assembles men from Estancia de la Virgen in order to count them and give out instructions. Barely visible at upper left is a nun who had shown up to distribute food to the refugees.

The refugees from Estancia de la Virgen were bewildered as to why their village had been destroyed. “We are all farmers,” one Indian said. “There are no guerrillas.”

The refugees from Estancia de la Virgen were bewildered as to why their village had been destroyed. “We are all farmers,” one Indian said. “There are no guerrillas.”

Another said, “We hope this shadow will go from our village because we are innocent.”

A mother and daughter from Estancia de la Virgen in one of the tents distributed to refugees.

After taking a photo of this mother and daughter, I bought a dozen eggs for them at a tienda in San Antonio las Trojes, but when I went to deliver them, she cried out and ran away, apparently not realizing why I had returned.

Nor were refugees from Estancia de la Virgen the only survivors of massacres I interviewed. On April 26, 1982, I traveled to the village of Chipiacul where Guatemalan soldiers had killed 20 residents the previous night. The victims had ranged in age from 13 to 80.

Many of them were shot to death in the village’s small, cement-block meeting hall. The soldiers then used the books from the village’s one-shelf library to build a funeral pyre in an unsuccessful attempt to dispose of the bodies. The survivors I talked with were still in shock and were mystified as to why Chipiacul had been targeted.

The Guatemalan civil war was fought off and on from 1960 to 1996 and cost roughly 200,000 lives, most of them civilian. What was the fighting all about?

After decades of repressive governments, Guatemala enjoyed its “Ten Years of Spring” from 1944 to 1954 under liberal leadership. But agrarian reforms in the early 1950s outraged the United Fruit Company, and it prevailed upon the Eisenhower Administration to intervene. The result was a June 1954 military coup carried out by a group of CIA-trained Guatemalan exiles and billed as stopping Communism from establishing a beachhead in Central America.

Guatemala has never fully recovered. Indeed, at the very time the Guatemalan army under General Ríos Montt was massacring more than 1,700 Ixil Mayans, the White House endorsed him. “President Ríos Montt is a man of great personal integrity and commitment,” said President Reagan in December 1982. “I know he wants to improve the quality of life for all Guatemalans and to promote social justice.”

Were he alive today, I’m sure Ronald Reagan would be pleased that Ríos Montt for the moment at least is still enjoying impunity.

‘Death to the Ears.’ This threatening guerrilla graffiti in San Agustin, El Salvador, was a warning to any would-be government informants. (1982)

‘Death to the Ears.’ This threatening guerrilla graffiti in San Agustin, El Salvador, was a warning to any would-be government informants. (1982)

‘I was his home for nine months. Now it’s provided by Clayeux [diapers.]’ A billboard in Paris, 1983.

‘I was his home for nine months. Now it’s provided by Clayeux [diapers.]’ A billboard in Paris, 1983.