Entries tagged with “The Light on the Coast”.

Did you find what you wanted?

Sun 10 May 2015

Posted by DavidMitchell under History

Comments Off on A trip to Tomales

The Light on the Coast: 65 Years of News Big and Small as Reported in The Point Reyes Light, has now sold out virtually all of its third printing. When I wrote the book a year and a half ago with Jacoba Charles as coauthor, I had no idea it would sell so well. Aside from a very few copies at Point Reyes Books, Toby’s Feed Barn, and Tomales Regional History Center, it’s no longer available in West Marin.

The History Center published it, and on Sunday Lynn and I drove to Tomales to drop off the last few copies still on hand. It would have been an easy jaunt were it not for all the bicyclists on Highway 1. Riding four abreast on a two-lane state highway would seem to be the height of either ignorance or arrogance, but at least on this trip we didn’t see any spandex-covered legs sticking out of the ditch.

While in Tomales, Lynn and I stopped at Mostly Natives Nursery to check out the posies, and Lynn found a giant verbena to add to the foliage on our deck. For those of you who aren’t familiar with it, Mostly Natives is a great little nursery right beside Highway 1 downtown. And as it happens, it’s also the setting of one of my favorite stories in The Light on the Coast.

In a March 3, 2005, news article headlined “Wild turkey blacks out Tomales,” Point Reyes Light reporter Peter Jamison wrote: “A surprisingly resilient wild turkey downed power lines in Tomales last week, causing a four-hour blackout. The turkey, by all indications, is still alive and at large.

“Tomales residents Margaret Graham and Walter Earle, owners of Mostly Natives, were drinking tea and reading the paper shortly before 6:45 a.m. last Friday in their home when they were startled by a loud explosion and brilliant flash of light from outside their window.

“Running outside, they discovered three downed power lines and a dazed-looking turkey walking in circles on Highway 1. The couple watched as the turkey ambled into the field across the road from their house, disappearing into the brush.

“‘He could have had a heart attack later on in that field,’ Graham said. ‘But I don’t know. There were some feathers in the road, but they didn’t look burnt.'”

“Earle immediately reported the downed power lines to the Tomales firehouse. ‘Some turkey just took out the power lines,’ he recalled saying. Fire Captain Tom Nunes told The Light that he assumed at the time that Earle was referring to a drunk driver rather than a bird.

“Arriving on the scene, Nunes and a crew of volunteer firefighters were baffled to find a mysterious scattering of feathers, but no turkey. After a search of the area yielded no dead or dying birds, Nunes could only confirm that the turkey had somehow survived a head-on collision with a 12,000-volt power line.

“‘You’d think where the power line broke there’d be a fried bird or something,” Nunes said, ‘but we couldn’t find remnants or anything.’

“The jolt of electricity administered to other birds, such as turkey vultures, that more commonly touch live power lines is so strong that the birds typically burst into flames, Nunes said. Typically this occurs when a vulture sitting on a line starts to take off, and its long wings touch two lines simultaneously. In one such accident in the summer of 1998, a flaming buzzard fell to the ground and ignited a 2.5-acre grass fire along Old Rancheria Road in Nicasio.

“Some 825 households and businesses in Tomales initially lost power when the blackout began at 6:45 a.m. Of these, 622 had their power back on by 8 a.m. All customers had their lights back on by 10:15 a.m., spokesman Lloyd Coker of PG&E said.

“Coker noted that he’s never heard of a bird surviving a brush with power lines, and he could recall only one instance when a wild turkey had flown into a power line, which happened about eight years ago in Sebastopol.

“‘I certainly wouldn’t say it’s a common occurrence,’ he added. The scarcity of such incidents is no surprise since wild turkeys can fly only short distances when they fly at all. ‘They don’t fly all that well, so we’ve had no [previous] cases of turkeys hitting the power lines,’ Nunes said.

“At the site of last week’s mishap, however, a steep hillside serves as a launching pad for the birds, which, frantically flapping their wings, can travel to the field across the road.

“Graham said she and her husband had often witnessed the birds in their short bursts of flight across the highway….”

This excerpt from Jamison’s news story is one example of why I as editor of The Light appreciated his craftsmanship. Nor was I the only editor who did. After he left The Light, Jamison went on to write for SF Weekly, The Tampa Bay Times, and now The Los Angeles Times, where he is the metro reporter.

Meanwhile, back in Tomales, nurseryman Walter Earle today shared his amused memories of that winter day 10 years ago when a wild turkey blacked out the town. In particular, he remembered firefighters preparing for a medical emergency when they thought the “turkey” he was talking about was a drunk driver.

Mon 24 Nov 2014

It was the best of times. It was the worst of times. I turned 71 Sunday, which was probably a good decision, but I threw out my back earlier in the week, which definitely was not a good move. You never realize how much use you have for something until you throw it out.

Just standing up is now a pain, and walking is even worse.

Doug Hill, president of the Berkeley City Commons Club, relays a member’s question to me at the end of my talk. (Photo by Dave LaFontaine)

As it happens, Morton McDonald, who has a home at Duck Cove in Inverness, had invited me to tell the Berkeley City Commons Club what I knew about Synanon from the cult’s days in West Marin. I had agreed to go last Friday but had to strut and fret my hour upon the stage from an overstuffed chair.

I’ve tried to portray my injury as caused by rugged work, telling friends I threw out my back while working with a chainsaw. “What were you cutting?” they ask. “Daisies,” I sheepishly reply. They’re inevitably startled. “No one throws out his back cutting daisies,” they say, “and no one cuts daisies with a chainsaw.”

It’s a long story. Former Point Reyes Light reporter Janine Warner and her husband Dave LaFontaine drove up from Los Angeles for my birthday and are staying for five days. My stepdaughter Kristeli, who is in her last year at New York University, will fly in Tuesday and stay for five days over Thanksgiving.

Vegetation was hanging over the railing along the outdoor steps, and I wanted everyone to be safe when they used the stairs. When I cut four or five dead fronds off a palm and three dead branches off a couple of pines, the chainsaw went right through them. But when I bent over to cut some woody branches from dead sections of two daisy bushes, a muscle spasm locked onto my back with all four feet.

Heating pads, back braces, and a ball-bearing-filled massage machine are helping, and I’ll no doubt recover in a week or two although post-traumatic-stress disorder could be a lingering problem.

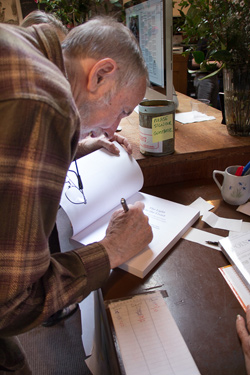

I sign a copy of The Light on the Coast for Morton McDonald. The book includes a section on the paper’s investigation of Synanon, an investigation that led to a Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. (Photo by Dave LaFontaine)

In the “best of times” category, The Light on the Coast: 65 Years of News Big and Small as Reported by The Point Reyes Light, which I wrote with Jacoba Charles as coauthor, is now in its third printing. The Tomales Regional History Center is the publisher, and the book can be ordered online using the History Center link in the righthand column.

Two blacktails butting heads outside my kitchen window last week. I’d think a deer could easily get an eye poked out that way, but I’ve never seen a buck with an eye patch.

Mon 21 Apr 2014

Posted by DavidMitchell under General News, History

Comments Off on America owes a lot to its weekly newspapers

Americans’ right to publish free from government interference is contained in the Constitution’s First Amendment, which was adopted in 1791. In the past 50 years, all manner of publications have relied on it in major court cases, ranging from the New York Times, which has used it as a defense against claims of libel, to Hustler magazine, which has used it as a defense against charges of obscenity.

But what did the founding fathers have in mind back in 1791 when they made freedom of the press a centerpiece of the First Amendment? They certainly were not thinking of radio or television. Neither had been invented yet.

Nor were they thinking of big daily newspapers, such as The Times. They didn’t exist either. There was no way to produce large-circulation newspapers back when presses were hand-powered. Mass-circulation newspapers weren’t possible before the first half of the 19th Century when, in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, steam-powered and then rotary presses appeared.

Nor was Congress thinking about men’s magazines, such as Hustler. There’d be no reason to before cameras were invented, and the earliest form of photography, daguerreotype, debuted in 1839.

The “press” America’s founding fathers sought to protect in 1791 consisted of weekly newspapers, often with circulations under 500 because that was the most that could be produced in a week’s time. These tiny papers were considered so crucial to America’s emerging democracy that nine of the original 13 states independently passed freedom of the press laws before Congress passed the First Amendment.

A dramatic example of the value that American colonists placed on their outspoken, highly partisan little newspapers occurred in 1765 when the British Stamp Act imposed a tax on newspapers and business documents, thereby shutting down many colonial newspapers. The public was furious. John Holt, the owner of New York’s Weekly Gazette and Post-Boy, found a warning letter thrown through the door of his print shop. “We are encouraged to hope you will not be deterred from continuing your useful Paper by groundless Fear of the detestable Stamp-Act,” the letter said.

“However, should you at this critical Time shut up the Press and basely desert us, depend on it, your House, Person and Effects will be in imminent Danger. We shall therefore expect your Paper on Thursday as usual.” Needless to say, Holt continued publishing.

It’s worth noting that despite today’s widespread calumny that “newspapers are dying,” most are not, and weeklies in particular are holding up well. Because thousands of US communities are too small to get regular coverage of local news from television and daily newspapers, weekly newspapers have a total nationwide circulation far larger than many people realize.

There are approximately 1,400 daily newspapers in the US. Together they have a total circulation of about 42 million. In contrast, there are well over 6,000 community newspapers, mostly weeklies, and they have a total circulation of roughly 65 million. All this according to the National Newspaper Association (NNA).

Unlike daily newspapers, weekly newspapers are not discarded after a day. Most weeklies sit around the house for several days with various household members picking them up multiple times. As a result, weekly newspapers are read by an average of 2.3 people per household, and they typically spend 38.95 minutes a week with each copy, meaning that 150 million people read a community newspaper almost 40 minutes a week, NNA reports.

Local news is the most-frequently read topic, and 73 percent of community-newspaper readers report reading all or most of each issue.

To be certain there are an increasing number of web-news sites, many of them maintained by newspapers, but their readers average only 4.4 minutes per visit, according to NNA. It’s also worth noting that 30 percent of adults who live where community newspapers circulate have no Internet access at home.

At 4 p.m. this Sunday, April 27, I’ll have more to say about the weekly press at Book Passage in Corte Madera.

At 4 p.m. this Sunday, April 27, I’ll have more to say about the weekly press at Book Passage in Corte Madera.

I’ll also read from my new book, The Light on the Coast: 65 Years of News Big and Small as Reported in The Point Reyes Light.

As the cover notes, the book is “the history of West Marin’s Lively Little Towns and their Pulitzer Prize-Winning Weekly Newspaper.”

It consists of news reports published at the time events were occurring plus a background narrative.

The Book Passage store where I’ll be speaking is located at 51 Tamal Vista Boulevard just north of Century Cinema theaters.

Tue 4 Mar 2014

During an open house and reunion Saturday, a happy throng of Point Reyes Light readers, staff, and columnists joined with former staff and correspondents to celebrate the 66th anniversary of the newspaper’s first issue.

The reunion drew staff and contributors who had worked at the paper at different times during the past 44 years. A number of former staff traveled hundreds of miles to attend. A couple of them arrived from out of state.

From left: Laura Lee Miller, David Rolland (who drove up from San Diego), Cat Cowles, Wendi Kallins, Janine Warner (who drove up from Los Angeles), Elisabeth Ptak (back to camera), Gayanne Enquist, Art Rogers (talking with Elisabeth), Keith Ervin (who drove down from Seattle), B.G. Buttemiller, and (in blue shirt with back to camera) Victor Reyes. (Photo by Dave LaFontaine) ______________________________________________________________

The party was also a celebration of the Tomales Regional History Center’s publishing The Light on the Coast: 65 Years of News Big and Small as Reported in The Point Reyes Light.

The party was also a celebration of the Tomales Regional History Center’s publishing The Light on the Coast: 65 Years of News Big and Small as Reported in The Point Reyes Light.

Stuart Chapman of Bolinas, a former member of the staff, shot this photo, which he titled “Dave, Proud Father” because I authored the book.

My co-author was Jacoba Charles. Jacoba reported for The Light under its previous ownership and is a member of the paper’s board of directors under its present ownership, Marin Media Institute.

The colored Post-its, by the way, mark selections that I, along with others, would be reading to attendees. ____________________________________________________________

From left: Co-author Jacoba Charles, photographer Art Rogers, scientist Corey Goodman, photographer David Briggs, editorial consultant on the book and former member of The Light’s ad department Lynn Axelrod, and Spanish-language columnist Victor Reyes. (Except where noted otherwise, the photos in this posting were shot by former Light reporter Janine Warner)

Michael Gahagan (left), who drove down from the Sierra Nevada town of Columbia to attend, published The Light from 1970 to 1975. Here he reminisces with historian Dewey Livingston of Inverness. Dewey for many years provided a weekly historical feature titled “West Marin’s Past.”

During the Gahagan years, Lee Sims (left) was the newspaper’s main typographer. This was back in the days before offset printing, and each page that went on the press had to be composed in lead.

In a piece written for The Light’s 30th anniversary in 1978 and reprinted in The Light on the Coast, Michael Gahagan’s former wife Annabelle comments, “Poor Lee, he had the disadvantage of being a friend of ours. One can always depend on friends, and we did lean on him! He was always underpaid and overworked. (Weren’t we all?)”

Catching up on old times are (in foreground from left): former news editor David Rolland, who drove to the reunion from San Diego, former typesetter Cat Cowles of Inverness, and former reporter Joel Reese, who flew in from Chicago. Standing behind them are current reporter Christopher Peak (left) and Matt Gallagher, who filled in as managing editor from February through July 2011. _____________________________________________________________

Samantha Kimmey (on the left) has been a reporter at The Light for the past year. With her is Tess Elliott of Inverness, who has been The Light’s editor for the past eight year. ____________________________________________________________

Samantha Kimmey (on the left) has been a reporter at The Light for the past year. With her is Tess Elliott of Inverness, who has been The Light’s editor for the past eight year. ____________________________________________________________

Gayanne Enquist was office manager during much of the 27 years I owned The Light. She was there when I arrived in July 1975, and she was there when I left in November 2005. (I was away reporting for the old San Francisco Examiner between September 1981 and the end of 1983.)

Former reporter Michelle Ling trades stories with Don Schinske, who was business manager during the 1990s and was co-publisher from 1995 to 1998. At left is her father, Dr. Walter Ling who teaches at UCLA. With his wife, May, Dr. Ling drove to Point Reyes Station for the celebration. In the background, Mary Papale listens intently to Laura Rogers.

Ingrid Noyes of Marshall (left) tells a story to my co-author, Jacoba Charles, outside The Light office.

Former staff recall the days of yore. From left: artist Laura Lee Miller, news editor David Rolland, typesetter Cat Cowles, reporter Janine Warner, and San Geronimo Valley correspondent Wendi Kallins. (Photo by Dave LaFontaine)

Sarah Rohrs was a reporter at The Light in the late 1980s. When several of us took turns reading aloud selections from The Light on the Coast, I read Sarah’s wonderfully droll account of a county fireman in Hicks Valley having to get a cow down out of a tree. (Photo by Joe Gramer)

Larken Bradley (left), who formerly wrote obituaries for The Light, chats with librarian Kerry Livingston, wife of Dewey.

Photographer Janine Dunn née Collins in 1995 traveled with news editor David Rolland to Switzerland’s Italian-speaking Canton of Ticino and to war-torn Croatia in doing research for The Light’s series on the five waves of historic immigration to West Marin. Here she chats with the paper’s current photographer David Briggs (center) and her husband John Dunn.

Former Light graphic artist Kathleen O’Neill (left) discusses newspapering in West Marin with present business manager Diana Cameron. _____________________________________________________________

Former Light reporter Marian Schinske (right) and I wax nostalgic while photographic contributor Ilka Hartmann (left), looks on and Heather Mack (center), a graduate student in Journalism at UC Berkeley, takes notes. ____________________________________________________________

Former Light reporter Marian Schinske (right) and I wax nostalgic while photographic contributor Ilka Hartmann (left), looks on and Heather Mack (center), a graduate student in Journalism at UC Berkeley, takes notes. ____________________________________________________________

Former news editor Jim Kravets (left) jokes with photographer Art Rogers.

John Hulls of Point Reyes Station and Cynthia Clark of Novato have in the past worked with The Light in various capacities. In 1984, Cynthia set up the first computer system for the newsroom and ad department.

From left: Stuart Chapman of Bolinas, who formerly worked in The Light’s ad department, swaps stories with journalist Dave LaFontaine of Los Angeles and Light columnist Victor Reyes.

Historian Dewey Livingston (left), a former production manager at The Light, poses with former news editor David Rolland while former business manager Bert Crews of Tomales mugs in the background.

In preparing to shoot one of his signature group portraits, Art Rogers directs members of the crowd where to stand. With the throng crowded into the newspaper office, getting everyone in the right place to be seen was such a complicated operation that some of the photographer’s subjects began photographing him. _____________________________________________________________

In shooting a series of three-dimensional photos, Art had to use a tall tripod and balance precariously on a window ledge and ladder. _____________________________________________________________

In shooting a series of three-dimensional photos, Art had to use a tall tripod and balance precariously on a window ledge and ladder. _____________________________________________________________

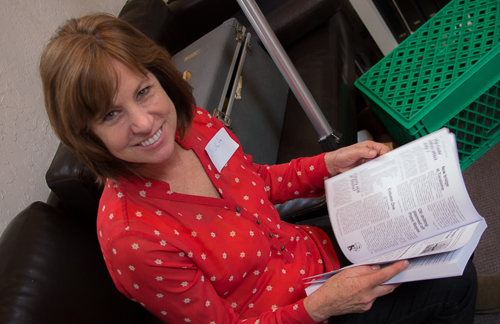

Art’s wife, Laura, who didn’t have to work nearly as hard, pages through a copy of The Light on the Coast. _______________________________________________________________

The party was in part a book-signing, and I signed copies off and on all afternoon. ______________________________________________________

The party was in part a book-signing, and I signed copies off and on all afternoon. ______________________________________________________

Light editor Tess Elliott reads Wilma Van Peer’s 1998 account of working for the paper’s founders, Dave and Wilma Rogers half a century earlier. The newspaper was called The Baywood Press when it began publishing in 1948. The paper’s fourth publisher, Don DeWolfe, changed the name to Point Reyes Light in 1966.

Originally the readings were scheduled to be held in the newspaper office, but so much socializing was going on they had to be delayed until the party moved around the corner to Vladimir’s Czech Restaurant where the banquet room had been reserved.

Among those reading besides Tess were Dewey Livingston, David Rolland, Matt Gallagher, and I. Anyone wishing to watch me read former publisher (1957 to 1970) Don DeWolfe’s account of his initiation to running the paper can click here.

It was a grand party, and I want to thank present Light staff, who made arrangements for the party, and former staff, some of whom traveled significant distances to attend the reunion.

Two other book readings are also scheduled. At 3 p.m. Sunday, March 9, in Point Reyes Presbyterian Church, Point Reyes Books will sponsor readings from The Light on the Coast and from Point Reyes Sheriff’s Calls, Susanna Solomon’s book of short stories inspired by Sheriff’s Calls in The Light.

At 4 p.m. Sunday, April 27, in its Corte Madera store, Book Passage will sponsor readings from The Light on the Coast. Refreshments will be served.

Tags: Art Rogers, B.G. Buttemiller, Baywood Press, Bert Crews, Cat Cowles, Christopher Peak, Corey Goodman, Cynthia Clark, Dave LaFontaine, Dave Rogers, David Briggs, David Rolland, Dewey Livingston, Diana Cameron, Don DeWolfe, Don Schinske, Elisabeth Ptak, Gayanne Enquist, Heather Merk, Ilka Hartmann, Jacoba Charles, Janine Dunn née Collins, Janine Warner, Jim Kravetz, John Dunn, John Hulls, Kathleen O'Neill, Keith Ervin, Kerry Livingston, Larken Bradley, Laura Lee Miller, Laura Rogers, Lee Sims, Marian Schinske, Matt Gallagher, Michael Gahagan, Point Reyes Light, Sarah Rohrs, Stuart Chapman, Tess Elliott, The Light on the Coast, VÃctor Reyes, Wendi Kallins

Tue 11 Feb 2014

Approximately 15 inches of badly needed rain fell in drought-stricken West Marin during the past week, with much of it falling last weekend.

Although the rain flooded numerous roadways, including sections of Highway 1, roughly 50 people showed up at Tomales Regional History Center Sunday to hear Jacoba Charles and me read a few selections from our book, The Light on the Coast: 65 Years of News Big and Small as Reported in The Point Reyes Light.

In December, the History Center published the book, which draws upon news coverage in The Light to tell the post-World War II “history of West Marin’s lively little towns and their Pulitzer Prize-winning weekly newspaper.”

Jacoba and I looked through more than 3,300 back issues in choosing representative selections of writing, photography, and political cartoons to include in the book. We then wrote background narratives for many of the news stories.

The crowd filled the History Center’s conference room, where awards and other mementos from the newspaper’s past were on display. After our readings, Jacoba and I signed copies of the book while directors of the History Center served refreshments. (Photos by Lynn Axelrod)

Jacoba started the readings with Wilma Van Peer’s 1998 account of working for the paper’s founders, Dave and Wilma Rogers, half a century earlier. Mrs. Van Peer described Dave as a “little man” with a “nose for news” who liked to “tease” people.

The Light, which was called The Baywood Press for its first 18 years, has had 10 sets of owners in the past 65 years. I published the paper for 27 of those years and wrote the chapters covering news from the first eight ownerships.

Jacoba reported for The Light during its previous ownership and is on the paper’s board of directors under today’s owner, Marin Media Institute. She compiled the chapters dealing with news coverage under the last two sets of publishers.

I unexpectedly found myself getting choked up while reading aloud an item from a June 22, 1950, column of social news:

“Mr. and Mrs. Anton Kooy and sons Peter, 13 years, and Walter, 11 years, have arrived at Blake’s Landing ranch from Amsterdam, Holland. They have come to join their friends Herbert Angress and Bill Straus, and Anton is going into business with Bill and Herbert. The Kooys will live at the Clark home, which the Harold Johnstones now occupy, near Marshall.

“During the last war, Mr. and Mrs. Kooy took Herbert Angress in to stay with them, thus saving his life from the Nazis. The two boys will be attending the Tomales schools, Peter being of high school age.”

While reading this short item to the crowd, I was once again struck by the horrendous danger in which Herb Angress had found himself and by the Kooy family’s heroism in putting themselves at risk to shelter him. Then, five years after World War II ended, they followed him to West Marin.

What choked me up was the sudden realization that when this potentially tragic drama came to a happy ending in Marshall, it made West Marin seem like part of a wartime miracle.

Jacoba reads the late historian Jack Mason’s account of former publisher Don DeWolfe changing the paper’s name from Baywood Press to Point Reyes Light in 1966. Full of wry humor, the story is set in the Station House Café, which Mason operated for awhile after he retired from an editor’s post at The Oakland Tribune.

Victor Reyes, who writes a Spanish-language column for The Light, filled in for Dewey Livingston during the readings.

The book’s designer, Dewey Livingston, lives in Inverness where he is the historian at the Jack Mason Museum of West Marin History. He had been scheduled to take part in the readings but had to bow out at the last minute. Second Valley Creek behind his house was flooding and undercutting his bedroom, forcing Dewey to stay home and deal with the rising water.

The Light on the Coast reprints the paper’s entire series on the five waves of ethnic immigration to West Marin during the past 160 years. To research the series, the newspaper sent reporters abroad four times in nine years, to Croatia, Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic, Switzerland’s Italian-speaking Canton of Ticino, Portugal’s mid-Atlantic Azores, and the Jalostotitlán region of Mexico.

Victor, who was one of the reporters on the immigration stories from Mexico, described Jalostotitlán and two neighboring towns. Most of West Marin’s Mexican-immigrant families hail from that area.

He stressed how traditional and conservative people are in Jalos (the city’s nickname) although it is only a 90-minute drive from Guadalajara. The priest virtually runs the city, Victor said.

West Marin’s non-Latino residents that are familiar with large Mexican municipalities, such as Mexico City, may think they understand the culture of Mexican-immigrant residents here, Victor said, but Jalos is a world apart, and the difference can sometimes lead to confusion.

Two more readings and book signings are scheduled in West Marin. From 3 to 6 p.m. Saturday, March 1, there will be a reading, a public open house, and a reunion of former Light staff in the newspaper’s new office behind the Inverness Post Office.

Point Reyes Books will sponsor a third reading and book signing at 3 p.m. Sunday, March 9, in Point Reyes Station’s Presbyterian Church.

Sun 8 Dec 2013

The April 12, 1956, edition of Point Reyes Station’s Baywood Press reported: “Mrs. Joe Curtiss’ television set caught fire last week, and the wall behind the set began burning.

“Before the fire department could answer the call, Margie picked up the set, threw it out the window, and proceeded to extinguish the blaze.”

That was the entire report, but Margie must have been a hardy soul because that early TV would have been big and heavy as well as hot.

The Baywood Press, as The Point Reyes Light was called for its first 18 years, began publication on March 1, 1948.

The Baywood Press, as The Point Reyes Light was called for its first 18 years, began publication on March 1, 1948.

The newspaper’s coverage of the past 65 years of West Marin news, big and small, is the focus of a book its publisher, the Tomales Regional History Center, has just released.

The book’s cover at left.

I’m particularly interested in the book, The Light on the Coast, because I, along with Jacoba Charles, authored it.

The graphic artist was Dewey Livingston, formerly production manager at The Light. He is now the historian at the Jack Mason Museum of West Marin History and is an historian for the National Park Service.

The Light is in its 10th ownership, Marin Media Institute, and the evolution of the newspaper itself is part of the story. As editor and publisher for 27 years, I was responsible for the chapters covering the first eight ownerships. Jacoba, who is on The Light’s board of directors and formerly was a reporter for the paper, was responsible for the most recent two.

Flooding in Bolinas. The ferocious storms that periodically hit the coast have always received extensive coverage in The Light.

Highlights of the 354-page book include the evolution of West Marin agriculture; the effects of the arrival of the counterculture on local politics, law enforcement, and the arts; the creation of the Point Reyes National Seashore and the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

Examples of The Light’s Pulitzer Prize-winning coverage of violence and other illegal activities by the Synanon cult are, of course, included in The Light on the Coast.

The newspaper’s complete series on the five historic waves of immigration to West Marin is also a central chapter.

The forefathers of many longtime families in West Marin arrived in immigrations from specific locales in: Ireland, Switzerland’s Italian-speaking Canton of Ticino, Croatia, and Portugal’s mid-Atlantic Azores. Researching their journeys to West Marin, as well as the more-recent immigration from Mexico, involved sending Light reporters abroad four times between 1988 and 1997.

This illustration for Sheriff’s Calls by cartoonist Kathryn LeMieux’s was often used in Western Weekend editions. The final section of our book consists of some of the more unusual Sheriff’s Calls from the the past 38 years.

This illustration for Sheriff’s Calls by cartoonist Kathryn LeMieux’s was often used in Western Weekend editions. The final section of our book consists of some of the more unusual Sheriff’s Calls from the the past 38 years.

The Light on the Coast features, along with a variety of news and commentary, a sampling of cartoons, advertising, and photography (including 10 portraits by Art Rogers). My partner Lynn Axelrod and I reviewed almost 3,000 back issues of The Point Reyes Light/Baywood Press in compiling the book. Jacoba reviewed more than 400. After making our selections, she and I wrote background narratives for many of them.

Those who’ve read the book have had good things to say about this approach of presenting West Marin’s history through the pages of The Light. Commenting on the book, San Francisco Chronicle reporter and columnist Carl Nolte writes: “The Point Reyes Light is a great window into a fabulous small world.”

Dr. Chad Stebbins, executive director of the International Society of Weekly Newspaper Editors, is likewise enthusiastic: “Dave Mitchell and The Point Reyes Light are synonymous with top-shelf newspapering. Dave is one of the few small-town editors ever to win a Pulitzer Prize; his investigation of the Synanon cult is a textbook example of tenacious reporting. His witty and colorful anecdotes always make for good reading.”

The Light on the Coast is available at Point Reyes Books for $24.95 plus tax.

It can be ordered online from the Tomales Regional History Center bookstore for $29.95 including tax and shipping.