Entries tagged with “Papermill Creek”.

Did you find what you wanted?

Sun 22 Mar 2015

Posted by DavidMitchell under General News, Point Reyes Station

Comments Off on Caltrans meeting about replacing Green Bridge draws mixed responses

A crowd of Tomales Bay area residents showed up at West Marin School Thursday to look over Caltrans plan to replace the Green Bridge in Point Reyes Station. The bridge carries an average of 3,000 vehicles on Highway 1 over Papermill Creek daily.

Caltrans would like to spend approximately $5.8 million to replace the 100-foot-long bridge, beginning in 2018 or 2019 and finishing three or four years later.

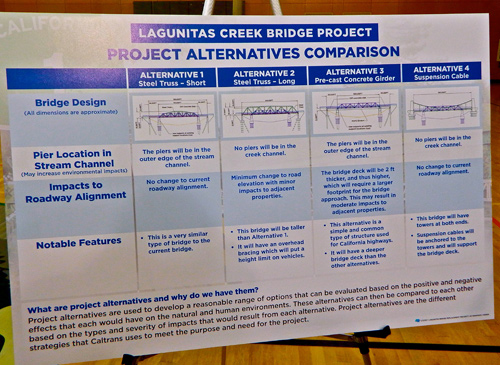

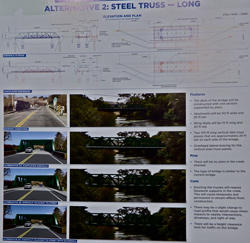

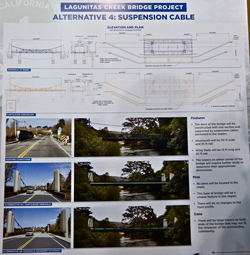

A team of Caltrans representatives were on hand Thursday to explain diagrams of four alternative designs for the replacement: a short, steel-truss bridge; a long, steel-truss bridge; a precast, concrete girder bridge; and a suspension bridge.

The underside of the Green Bridge.

“The current bridge was determined to be seismically deficient, and retrofitting the bridge was deemed infeasible due to limitations caused by the nature of the original structure,” Caltrans reported earlier. The bridge was built in 1929.

The alternative designs differ in: how the piers will affect the creek channel, affect neighboring properties, and alter the approaches to the bridge. They also differ in bridge height and in the thickness of the deck.

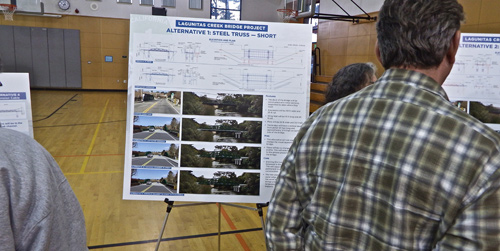

The short-steel-truss design is “very similar” to the present bridge, Caltrans says. ________________________________________________________________

The long-steel-truss design would be taller than the existing bridge.

The long-steel-truss design would be taller than the existing bridge.

It would have overhead bracing, which would put a limit on the height of vehicles that could use it.

Approximately 120 of the vehicles that now cross the bridge each day are trucks.

____________________________________________

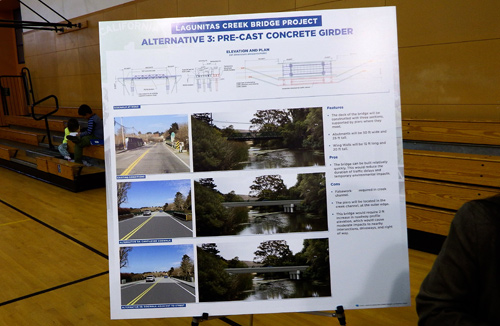

Under this alternative, the bridge deck would be two feet thicker than it presently is. It would also cover more land and water, and this would have “moderate impacts to adjacent properties,” Caltrans noted. _______________________________________________________________

The suspension-cable design under consideration would have towers at each end, anchoring the cables supporting the bridge deck.

The suspension-cable design under consideration would have towers at each end, anchoring the cables supporting the bridge deck.

There would be “no piers” in the creek and there would be “no change to the current road alignment,” according to the state.

______________________________________________________________________

A spot check of residents attending Thursday’s meeting found many people skeptical of the need to replace the bridge but resigned to it.

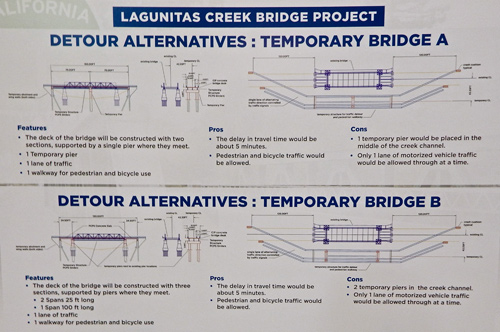

The hot-button issue was what will happen to traffic on Highway 1 and the intersecting levee road during the estimated 18 to 24 months of rebuilding. Caltrans has two alternative proposals for a temporary bridge, but each would be able to accommodate only one direction of traffic at a time.

Provision would be made for bicycle and pedestrian traffic, and a stoplight would be installed to regulate vehicle traffic. Vehicle delays would be “about five minutes,” the highway department predicted. The traffic jams on a summer weekend would be huge, numerous people warned.

A bridge too far?

Coming in for virtually no discussion was a smaller bridge about 60 yards north of the Green Bridge. This Highway 1 bridge was also built in 1929, but no mention was made of its condition.

Another bridge too far?

Also left unmentioned was a second small bridge, which is about 50 yards south of the Green Bridge near Marin Sun Farms. What’s the condition of its piers? I wasn’t about to wade around in the muck to find out.

A “draft environmental document will be made available for public review and comment in mid-2016,” according to Caltrans. “The final environmental document is expected to be issued by early 2017, and design completion will be in late 2018.

“Construction is expected to begin in three to four years and last approximately two to three years.”

People wanting to have their concerns considered in Caltrans’ planning can write the state at: <lagunitas_bridge@dot.ca.gov>.

Mon 16 Mar 2015

Caltrans plans to hold a public meeting from 7 to 9 p.m. this Thursday, March 9, at West Marin School to discuss replacing the Green Bridge which carries Highway 1 over Papermill Creek in Point Reyes Station.

You’re familiar with Caltrans’ bridge work, I’m sure. Its star-crossed replacement of the eastern span of the Oakland Bay Bridge has become an endless story in the Bay Area news media.

Caltrans, which wants to spend $5.8 million replacing this bridge, says it has come up with four designs for a new one. The public will have a chance Thursday to comment on them.

In the mid-1800s, Olema was a far busier place than Point Reyes Station, and a ferry carried travelers going back and forth between the two towns. In 1875, the County of Marin built the first bridge in this location. Its modern replacement was obviously built in 1929.

This 100-foot-long span on Highway 1 carries approximately 3,000 vehicles per day, 4 percent of them trucks, Caltrans reports. The 10,000-foot-long Bay Bridge on Interstate 80 in comparison carries about 240,000 vehicles per day between Oakland and San Francisco.

Caltrans questions whether the 24-foot-wide Green Bridge is earthquake safe, saying its structure is okay, but its “deck geometry” is “basically intolerable.”

1959 photo by D.M. Gunn, courtesy of Dewey Livingston

The old Tocaloma Bridge was built in 1927 to carry Sir Francis Drake traffic over Papermill Creek in the town of Tocaloma, which lies 1.8 miles east of Highway 1 at Olema. The bridge was designed by J.C. Oglesby.

Oglesby also designed the matching Alexander Avenue bridge still in use in Larkspur. (Wikipedia Commons photo)

Oglesby’s old Tocaloma Bridge as it looks today.

The new Tocaloma Bridge carrying Sir Francis Drake traffic over Papermill Creek is immediately upstream from the old bridge. The state built the new bridge in 1962 at a cost of $210,000.

San Antonio Creek forms the boundary between Marin and Sonoma Counties, as seen from the Point Reyes-Petaluma Road while heading west.

The San Antonio Creek Bridge along the Point Reyes-Petaluma Road straddles the Marin-Sonoma county line just east of Union School.

The 102-foot-long bridge over San Antonio Creek was built in 1919 and replaced in 1962.

The continuous-concrete-slab construction of the 1919 bridge still looks solid. However, the bridge’s width and deteriorating pavement brought about its being replaced with the wider, better-paved bridge beside it.

When I set off to shoot these photos, I was well aware that West Marin’s abandoned bridges are in scenic locales, but this view from the old San Antonio Creek Bridge was, nonetheless, a pleasant surprise.

If Caltrans has its way, the Green Bridge will likewise be abandoned in the near future. Will it then become an historic relic like these? Or will it be cut up and sold as scrap iron?

Mon 2 Jun 2014

White House Pool, which is maintained by the County of Marin, is my favorite park in West Marin. The park, which is midway between Point Reyes Station and Inverness Park, includes a few picnic tables and open areas, but mostly it consists of a beautiful trail along Papermill Creek. The “pool” is basically a wide bend in the creek.

Point Reyes Station and Black Mountain as seen from White House Pool.

Here’s its story. A “fast-talking” developer named Isaac Freeman “began hawking lots in 1909” in a tract that was to become Inverness Park, to quote the late historian Jack Mason. “White House Pool, just south of the Park, was a watering place where Freeman had bathhouses, water tank, windmill, and tract office.”

The path through the park has become popular with dog walkers, most of whom responsibly bag their pooches’ poop.

The name “White House” has nothing to do with the US capital. Rather it refers to a white building that at different times played significant roles in the area’s history. It was “one of the oldest houses on Point Reyes,” Mason wrote in Earthquake Bay. “Edward I. Butler [1874-1961] lived in it as a boy before going on to a career on the bench and in politics.”

Butler would become the San Rafael city attorney; would serve two terms in the California Assembly; would go on to be elected Marin County district attorney; was appointed and then repeatedly reelected to the Marin Superior Court bench, serving 31 years. All this according to the County of Marin website.

One of the county’s greatest challenges in maintaining the park is controlling its abundant poison oak. Pacific poison oak is naturally rampant throughout West Marin, and unfortunately most humans have allergic reactions to touching its oil and to inhaling its smoke during fires. Common reactions are rashes, blisters, and intense itching.

“World War II gave the [white] house new importance as an Army communications center. Telephone Company employee Earl Hall, who rented it, took calls incoming from the Pacific Theater on his telephone, one of the few around,” Mason wrote. “His wife Avis recalls messages from the big White House coming through her little one!

“A soldier with fixed bayonet stood outside searching cars for possible Japanese infiltrators.”

The pedestrian bridge near the White House Pool parking lot at times is so overgrown with poison oak that it takes care not to brush against it.

After the war, the building evolved into a lightly used fishing cabin. “When the white house… fell into disrepair, owners William and Lloyd Gadner, reacting to a county order they either bring it up to ‘code’ or demolish it, chose the latter,” Mason wrote. “I have rueful memories of that 1969 morning, holding off Walter Kantala’s bulldozer while I hurried home for a camera.”

Among the delights of the White House Pool trail are a series of side-paths through more poison oak mixed in with other foliage. (You can avoid the bad stuff if you’re at all careful, and it’s worth the effort.) These paths lead to clearings on the creek bank where a walker can rest on a bench while enjoying views of the foot of Tomales Bay.

For those wanting to keep further away from any poison oak, there are also a few benches in open areas.

As Lynn observes, Marin County Parks and Open Space Department periodically cuts back the poison oak that protrudes through the railing of the White House Pool footbridge. A member of the department staff on Monday told us the frequency of cutting depends on what staff observe and what the public reports to the county.

On Monday, however, the staffer’s main concern was not poison oak but a vandal who over the weekend managed to drive around the barricades at the edge of the parking lot in order to “spin donuts” in dry grass. I doubt the jerk will ever be identified, but if he is, he ought to be sentenced to clearing poison oak at White House Pool.

Sat 24 Mar 2012

Posted by DavidMitchell under General News, Marin County, Point Reyes Station

Comments Off on A drought for livestock but not for people

Water sheets down Seeger Dam as Nicasio Reservoir overflows.

A week after Nicasio Reservoir overflowed March 13, county supervisors declared an agricultural emergency because of drought conditions afflicting Marin ranches. The supervisors’ resolution declaring the emergency is the first step toward getting federal aid for ranchers.

Marin County Agricultural Commissioner Stacey Carlsen told the supervisors rainfall at many dairy and livestock ranches has been 31 percent of normal. The low rainfall combined with unseasonably warm weather, strong winds, and frosty mornings has dried out grass and inhibited new growth, the agricultural commissioner explained.

The forage losses in pastures and rangelands are roughly 50 percent, he estimated. This has forced ranchers to reduce herd sizes and to buy supplemental feed far earlier in the year than usual, Carlsen said. The cost of feed is continuing to rise, the agricultural commissioner noted, and this is having a severe impact on Marin ranches. This county’s ranches, he said, are already operating with narrow margins.

Nicasio Reservoir water rushes down the spillway below Seeger Dam and flows into nearby Papermill Creek.

Notwithstanding the drought affecting ranches, the big water districts in West Marin report they’re doing just fine, thank you very much. Already this month, West Marin has received almost 15 inches of rain. As of a week ago, Marin Municipal Water District’s seven reservoirs stood at 94 percent of capacity compared with 91 percent at this date in an average year.

Even before this weekend’s rainstorms, Libby Pischel, spokeswoman for Marin Municipal, told me, “We are not expecting any rationing [this year].” The MMWD system serves homes and businesses in the San Geronimo Valley and in most of East Marin south of Novato.

Novato-based North Marin Water District operates a satellite system serving Point Reyes Station, Inverness Park, and Olema. It gets its water for the system from wells beside Papermill Creek upstream from the Coast Guard housing site in Point Reyes Station. Most of the water feeding the wells originates in two MMWD reservoirs: Nicasio Reservoir seasonally and Lake Lagunitas year round. A small amount originates in San Geronimo Creek.

North Marin General Manager Chris DeGabriele on Friday told me, “We are not expecting any water restrictions next summer in West Marin.”

Despite there being plenty of water to satisfy homes and businesses in three small towns, as well as fish in the creeks, there is not nearly enough to irrigate hundreds of square miles of ranchland — even if there were pipelines for doing so. Hence the agricultural emergency.

The long-steel-truss design would be taller than the existing bridge.

The long-steel-truss design would be taller than the existing bridge. The suspension-cable design under consideration would have towers at each end, anchoring the cables supporting the bridge deck.

The suspension-cable design under consideration would have towers at each end, anchoring the cables supporting the bridge deck.