Entries tagged with “buzzards”.

Did you find what you wanted?

Mon 11 Jul 2022

Caveat lectorem: When readers submit comments, they are asked if they want to receive an email alert with a link to new postings on this blog. A number of people have said they do. Thank you. The link is created the moment a posting goes online. Readers who find their way here through that link can see an updated version by simply clicking on the headline above the posting.

Headline in July 1 San Francisco Chronicle. I’ve been wondering in recent years whatever happened to Life magazine. Is this a clue?

Outside our kitchen, an appropriately named “wake” of eight buzzards (aka vultures) takes a rest while on a search for corpses.

Outside our kitchen, an appropriately named “wake” of eight buzzards (aka vultures) takes a rest while on a search for corpses.

As a 35-year newsman, I’ve covered a lot of grim news, such as the trailside killer in Marin County and combat in El Salvador. Nonetheless, I’ve been unsettled by the current combination of news from around the world: the Covid pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, mass shootings (which have killed more than 300 Americans already this year), the US Supreme Court’s overturning Roe v. Wade abortion rights, the court’s also revealing plans to throw out a number of environmental protections.

For my own peace of mind, I’m turning my attention to goings on in the animal world around Mitchell cabin. Here’s a bit of what I’ve been seeing.

Two quail watching over nine of their chicks. (Photo by Lynn Axelrod Mitchell)

Two quail watching over nine of their chicks. (Photo by Lynn Axelrod Mitchell)

A raccoon appearing to be in prayer. She’s probably praying that the chaos in the human world doesn’t also devastate the animal world.

A great blue heron hunts in our field for gophers. (Photo by Lynn Axelrod Mitchell)

Mother raccoons have taught their kits to show up on our deck each evening in hopes of receiving handfuls of kibble. The kits are shy but curious and sometimes show up by themselves (as these four did on Sunday afternoon) hoping for food even though mom wasn’t there yet.

A raccoon mother climbs down out of a pine tree beside Mitchell cabin while her kit prepares to follow her.

It’s this sort of domesticity in nature that gives me relief from our human world.

Fri 19 Feb 2021

Posted by DavidMitchell under Uncategorized

Comments Off on Looking animals in the eye

This week we’ll look animals, both domestic and wild, in the eye to get a sense of what they see.

Newy, the stray cat we’ve taken in and who has been mentioned here before, can have an intense gaze when she’s looking off at something. It’s noticeable enough that it prompted me to look into, so to speak, the eyes of not only cats but other animals as well. A cat’s vision is not as all-powerful as it appears. A cat is most sensitive to blues and yellows and does not see colors like red, orange, or brown.

A blacktail doe looks up from grazing outside our bedroom window. The pupils in a deer’s eyes are horizontal, not round, and a flash camera makes them look blue.

A coyote displays his predatory nature as he stares into a field. As it happens, just now as I type this, coyotes are howling outside Mitchell cabin. (Photo by neighbor Dan Huntsman)

The no-nonsense look of a bobcat in the field below Mitchell cabin.

Foxes too are predatory, but their gaze makes them appear more curious than vicious.

Possums have good night vision but don’t distinguish between colors very well. Overall, their vision is so weak they must depend on smell and touch to find food.

Skunks, like possums, have very poor vision and navigate largely via their senses of smell and hearing.

Wild turkeys, on the other hand, see in color and “have an excellent daytime vision that is three times better than a human’s eyesight and covers 270 degrees,” according to ‘Facts about Wild Turkeys.’ “They have poor vision at night, however, and generally become warier as it grows darker.”

‘Livingbird Magazine’ reports that “Great Blue Herons can hunt day and night thanks to a high percentage of rod-type photoreceptors in their eyes that improve their night vision.” Near Mitchell cabin, a gopher with the baleful stare of death hangs from the heron’s beak.

Buzzards have such “keen eyesight,” Seaworld claims, that “it is believed they are able to spot a three-foot carcass from four miles away on the open plains.”

A stern stare. Coopers Hawks are skillful hunters and like other hawks have excellent vision.

The smirk of a Western Fence Lizard (also known as a Blue Belly for obvious reasons). It’s one of the most common lizards around Mitchell cabin. As for their vision, most lizards have excellent eyesight, and some can see into the UV spectrum.

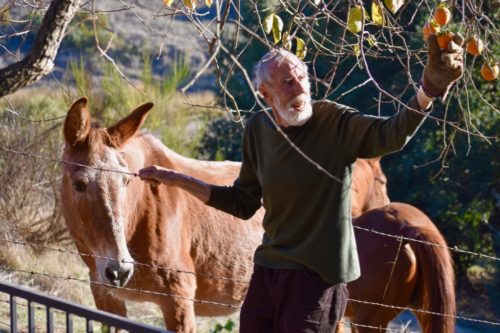

Somehow my work glove hand ended up on the persimmon, and my bare hand on the barbed-wire fence. (Photo by Lynn Axelrod Mitchell)

This moment became a test of my vision and not in looking at the persimmons growing between the fields of Mitchell cabin and Arabian Horse Adventures. After some staring, I concluded that the Arabian waiting patiently for a persimmon is, in fact, a female mule. Nonetheless, I eventually gave her some fruit. Later I found out the mule had arrived in the pasture not long ago after its owner died. So far I’ve never seen any of the stable’s trail riders on it. Arabian Mule Adventures.

Tags: animal eyesight, blacktail deer, blue belly, buzzards, Cooper's hawk, foxes, Great blue heron, jackrabbit, mule, possum, skunks, Western fence lizard

Mon 21 Sep 2020

Posted by DavidMitchell under Point Reyes National Seashore, West Marin nature, Wildlife

Comments Off on Home sometimes seems like an animal shelter

Caveat lectorem: When readers submit comments, they are asked if they want to receive an email alert with a link to new postings on this blog. A number of people have said they do. Thank you. The link is created the moment a posting goes online. Readers who find their way here through that link can see an updated version by simply clicking on the headline above the posting. All other readers already have an updated version.

Sheltering in place with only limited socializing definitely affects one’s thinking. It forces many of us to spend more time alone taking stock of ourselves and of our lives. It’s a humbling experience and may provide an inkling of why a prisoner behind bars cannot avoid thinking about his life. But, as I’m sure the prisoner knows, too much such thinking becomes tedious. For the moment, I’m trying to divert my attention to the creatures I find all around me.

A hummingbird a week ago enjoyed a few sips before the smoke from the Woodward Fire significantly dissipated. As of this writing, the fire, which a lightning strike started on Aug. 18, was 97 percent contained, having blackened 4,929 acres in the Point Reyes National Seashore.

A coyote wandered up to the greenhouse of neighbors Dan and Mary Huntsman on August 21. Had I been looking out my living-room window, this is what I would have seen. Alas, I wasn’t looking, but Dan was and from his home took this picture. (Photo by Dan Huntsman)

Buzzards on Sept. 13 feast on the carcass of a skunk presumably killed by a great horned owl. It was the second time in recent weeks buzzards dined on a skunk near Mitchell cabin.

A gray fox showed up on our deck after dark last week to dine on the last bits of kibble I had given some raccoons earlier.

A skunk goes eye to eye with Newy, the stray cat we adopted in late July. More frequently than the fox, skunks show up after the raccoons to pick through what remains of the kibble.

And in a weather vein: Whenever Lynn opened the bedroom window in recent days, I started sneezing and then coughing. “Do you think it’s pollen or smoke that’s causing the sneezing?” she asked me a couple of days ago. “The answer,” I told her, “is blowing in the wind.”

I’ll stop here. There’s a lot I’m tempted to write about our political situation, but I think I’ll save that for another week.

Wed 15 Jul 2020

Posted by DavidMitchell under Photography, Point Reyes Station, West Marin nature, Wildlife

Comments Off on Owls, buzzards, and other skunk eaters

Caveat lectorem: When readers submit comments, they are asked if they want to receive an email alert with a link to new postings on this blog. A number of people have said they do. Thank you. The link is created the moment a posting goes online. Readers who find their way here through that link can see an updated version by simply clicking on the headline above the posting.

Six buzzards landed on the hill above Mitchell cabin last Saturday, immediately letting Lynn and me know that something had died.

We could see one buzzard tearing away at a carcass. But of what?

(Before going further, I should acknowledge the “buzzard” v. “vulture” dispute I occasionally get into with a few readers who apparently prefer British English to American English. For them, vulture is the only correct name for the species, and buzzard means only Buteo hawk. I disagree, and my authority is The American Heritage Dictionary. It defines the word buzzard as: “1. Any of various North American vultures, such as the turkey vulture. 2. Chiefly British. A hawk of the genus Buteo, having broad wings and a broad tail. 3. An avaricious or otherwise unpleasant person.”)

Upon closer inspection (despite the stench) I could see the deceased was a skunk. My guess is that it was killed by one of the great horned owls on this hill. Because of the likelihood of getting sprayed, coyotes and foxes reluctantly hunt skunks only when no other prey is available. Great horned owls, whose weak sense of smell is limited to supplementing their sense of taste, like to hunt skunks.

A great horned owl. (Missouri Department of Conservation photo)

Female skunks typically raise four to six kittens in a season, with the males leaving the females before the young are born. Skunks were once widely hunted for their pelts, but they now have far more to worry about from motor vehicles; skunks are so near-sighted they can’t see things clearly that are more than 10 feet away.

This buzzard arrived a day late for Saturday’s feast but still found enough skunk flesh to nibble on. Buzzards are fond of dead skunks, but they leave the skunks’ scent pouches intact.

Raccoons, like dogs, identify each other by sniffing bottoms, and (as seen here before) they also sniff skunk bottoms but for some reason don’t get sprayed. Two nights ago I saw a very young kit repeatedly sniff a skunk’s rear end. The skunk didn’t like it and kept moving away, but the kit persisted in nosing around back there until the skunk finally walked away.

At least it didn’t get killed and partially eaten by an owl with most of the leftovers consumed by a flock of buzzards.

Sun 18 Jan 2015

Here is a gallery of my bird photography, as was promised two weeks ago. The photos were all shot at Mitchell cabin or around it.

One reason Mitchell cabin gets quite a variety of birds and other wildlife is that its fields come within a few feet of a neighbor’s stockpond, where numerous creatures show up daily to drink or hunt. Here a common egret wades through shallow water, looking for frogs, small fish, or insects.

While it’s hunting, a great blue heron will repeatedly stand motionless and then use lightning-fast strikes with its sharp bill and long neck to catch gophers in Mitchell cabin’s fields or frogs and fish in the pond.

The cabin is under the commute route for Canada geese which travel daily between the Point Reyes National Seashore and the Marin French Cheese Factory’s ponds in Hicks Valley. It’s easy to tell when they’re coming; they honk as much as Homo sapiens commuters stuck in traffic.

A flock of tri-colored blackbirds swoop down onto the deck railing when Lynn or I spread a line of birdseed along it morning and evening. Many of the blackbirds nest in reeds at the pond.

Even after they’ve grown old enough to feed themselves, young blackbirds for awhile still want to be fed by their parents. Once in awhile the parents do oblige them, but over a few days, they wean their youngsters. (Photo by my partner Lynn Axelrod)

A tom turkey struts his stuff. In 1988, a hunting club working with the State Department of Fish and Game introduced non-native turkeys into West Marin on Loma Alta Ridge, which overlooks the San Geronimo Valley. By now there are far more turkeys than turkey hunters, and their flocks have spread throughout West Marin.

A little more than a year ago, a lone peacock showed up and soon began hanging out with a flock of wild turkeys. Months later, he can still be seen bringing up the rear as the flock hunts and pecks its way across the fields.

A male quail. Male and female quail both have crests. The males’ crests are black, the females, brown.

The Eurasian collared dove is a native of the Middle East that spread across Europe in the 20th Century, according to the Audubon Society. In 1974, it was accidentally introduced into the Bahamas. In the 1980s, the doves discovered the US was only a short flight away and began taking trips to Florida. In less than 30 years, the doves have spread throughout most of this country.

California western scrub jays show up immediately when we put seed on the railing.

A California towhee freshens up in the birdbath on the deck.

Rufous-sided towhees are among the most colorful birds that show up for birdseed.

A purple finch chews a sunflower seed it found among other seeds on the railing.

The presence of golden-crowned sparrows is often announced by their song, which sounds like Three Blind Mice in a minor key.

Oregon juncos keep a close eye on Mitchell cabin’s deck, and it’s never long after we put out birdseed that they begin showing up. They’re less skittish than most other birds and will sometimes begin pecking seeds off the railing before we’ve departed.

A female hummingbird. Hummingbirds drop by for drinks whenever we have flowers in bloom.

American crows, which are native to North America, are considered intelligent birds. Here, for example, they demonstrate their mastery of jitterbug.

A crow skins its caterpillar dinner in the birdbath.

Redtailed hawks dine on reptiles, small mammals, and birds. Their call is a two-or-three second scream which trails downward. Redtails are monogamous and typically reach sexual maturity at age two or three and can live to age 21 in the wild.

When I spotted this great-horned owl in a tree 200 feet or more from the cabin one evening, I decided to try photographing it. However, the light was so low that when I triggered the shutter, the little flash on my old-fashioned Kodak flipped open and fired. To my amazement, the flash was reflected in the owl’s eyes despite the bird’s distance from me. With eye shine (see tapetum lucidum) like that, it’s no wonder owls can see well in the dark.

Two buzzards warming themselves in the morning sun.

This gallery doesn’t include all the birdlife around Mitchell cabin, of course, but it’s a sampling of our avian neighbors. They’re not the only reason I enjoy living where I do, but they’re a big part of it.

Tags: American crow, buzzards, California western scrub jay, Canada geese, common egret, Eurasian collared dove, Golden-crowned sparrow, Great blue heron, great-horned owl, purple finch, quail, redtailed hawk, Rufous-sided towhee, towhee, Tricolored Blackbirds, wild turkeys

Sun 13 Oct 2013

Posted by DavidMitchell under West Marin nature, Wildlife

Comments Off on A dead buck, buzzards, flies…. and who else?

Saturday morning I got a call from my neighbor Jay Haas, who told me, “If you’ve been wondering about all the vultures around here for the past day, there’s a dead deer on your side of our [common] fence. I thought you might want to snap a photo.”

I’d been over the hill all day Friday and hadn’t seen the buzzards, I replied, but I immediately went down to the fence to take some pictures. (Warning: three of the following photos are fairly grim.)

It wasn’t hard to figure out where the dead deer was. The first thing I saw was this buzzard sitting on a fence post warming itself in the morning sun and looking like the imperial eagle on Kaiser Wilhelm’s banner.

Most of the flesh, hair, and internal organs of the deer, a one- or two-year-old blacktail buck, had already been stripped from its skeleton. The bones, ears, antlers, and the hair on its head were about all that remained. There was no way to readily tell how it had died: killed by a predator, injured in traffic, wounded by a hunter, or weakened by disease.

By now the buzzards were circling overhead again, waiting for me to absent myself so they could carry on eating carrion.

Buzzard, by the way, is American English for vulture. My ornithologist friends periodically tell me I should be calling the birds vultures. Buzzard refers to a buteo hawk, they insist, not a vulture.

But that’s not what the dictionary says. My American Heritage Dictionary defines buzzard as “any of various North American vultures, such as the turkey vulture.”

The use of buzzard to mean buteo hawk, the dictionary adds, is “chiefly British,” and I don’t live in England. I live in the American West, and when a fellow here calls a disreputable man an old buzzard, he sure as hell doesn’t mean an old buteo hawk. He means an old carrion eater.

Two buzzards keep an eye on the carcass as two others strip some remaining bits of meat from the skeleton.

Buzzards aren’t the only creatures, of course, that dine on carrion, and it wasn’t obvious who had eaten most of the deer.

Buzzards aren’t the only creatures, of course, that dine on carrion, and it wasn’t obvious who had eaten most of the deer.

Foxes, raccoons, and coyotes eat roadkill and other dead animals.

Mountain lions will also eat carrion when extremely hungry but normally prefer fresh meat.

Smaller carrion eaters often start with the eyes and anus because they provide easy access to the rest of the body. These holes also open passages for flies.

The role of carcasses in a fly’s lifecycle is remarkable. The average lifespan of houseflies is only three weeks, but females can lay 900 eggs in that brief period. The eggs are laid in whatever the flies are feeding on, and within a day, the first larvae (also called maggots) hatch out. It takes less than two days for the maggots to double in size, forcing them to molt and shed their exoskeletons.

After continuing to grow, and molting two more times, the worm-like maggots dig deeper into their food supply and begin their pupa stage. The pupa develops a hard shell and inside it the appendages of an adult fly. To free itself from the shell, however, requires a strange ability. The pupa grows a bump on its head which it uses to break through the shell, after which the bump is absorbed back into the fly’s head. From a newly laid egg to an adult fly on the wing takes a week to 10 days in warm weather.

Before long five buzzards were perched on fence posts, watching two others tearing away at the carcass.

Sunday morning, I decided to take another look at the skeleton and was startled by what I saw. During the night, the buck had been dragged 10 feet uphill from the fence. Now who did that? Certainly not a buzzard, fox, or raccoon. Even stripped of most of its flesh, the skeleton was still fairly heavy.

I know of only two wild animals hereabouts with the strength to drag that much weight even a short distance: a mountain lion and a coyote. Although mountain lion tracks have been found near Mitchell cabin, there certainly aren’t many cougars hereabouts. Nor could I imagine a mountain lion going to the trouble of dragging around a skeleton that didn’t have much meat on it.

That would seem to leave one of the local coyotes as the most likely suspect. Coyotes, like mountain lions, sometimes drag their dinner to places where they can eat in private, but this coyote apparently gave up after only a few feet.

I called Jay back and asked if he had heard any coyotes howling Saturday night. He hadn’t but was as surprised as I that the skeleton had been moved.

The cause of the young buck’s death remains a sad mystery. The full variety of critters that ate its carcass is likewise a mystery. But who dragged its skeleton uphill is the biggest mystery of all.

Mon 30 Jul 2012

Posted by DavidMitchell under West Marin nature, Wildlife

Comments Off on Wild scene from my deck as photographed over two weeks

Not all wildlife has fared as poorly as bears, wolves, and buffalo in the wake of the settlers spreading their brand of civilization across America. Indeed, the deck of Mitchell cabin bears testimony to how well other creatures have adapted to changed environs. Here’s a look at wildlife photographed on or from the deck during two weeks in July.

From the limbs of a pine tree, three young raccoons observe activity on the deck below. The raccoons around Mitchell cabin rarely ransack trash cans in search of garbage to eat. Ick! They instead supplement their foraging with nightly stops on the deck for rations of dog kibble.

For the past several weeks, mother raccoons have been introducing their new kits to the nightly repasts on my deck. That happens every summer. This year, however, the kits have taken to wrestling on the deck after dining. Here one kit struggles on its back after being tackled by a sibling.

It’s great fun to watch although the wrestling occasionally lasts well into the night, and it’s not unusual for Lynn and me to be awakened by the sound of outdoor furniture being knocked around. Worse yet is the damage they do to our flowers, as the rough-housing sometimes takes the kits into our planters. The youngster at left is sparring with a fourth kit that’s behind the planter barrel.

A young raccoon climbs down lattice in getting off the railing. Raccoons have the ability to twist their rear paws to point backwards. This greatly enhances their climbing because they can hang from their rear claws as they descend.

Red-winged blackbirds flock to the deck each evening when Lynn or I scatter birdseed on the railing and picnic table. By some estimates, the red-winged blackbird is the “most-abundant and best-studied bird in North America.”

Male redwings are all black except for a red bar and yellow patch on the shoulders while females are a nondescript dark brown.

Given his stately bearing, it’s appropriate that the California quail is the official state bird of California.

Pecking seeds. Here’s another look at the colorful head and tail of the male quail (at bottom). The female (at top) is less colorful but also has a crest. In between are two of their chicks. As with fawns, spots help camouflage young quail.

A march of quail chicks, with their mother (bottom left) keeping an eye out for trouble.

A rufus-sided towhee eats birdseed off the picnic table. The towhees breed from Canada to Guatemala and typically have two broods a year. The male helps feed the chicks, which fledge (can fly) in 10 to 12 days.

A White-tailed kite glides over my field while hunting for rodents. (They rarely eat birds.) Although the White-tailed kite was on the verge of extinction 75 years ago in California as a result of shooting and egg collecting, white-tails have now recovered to where their survival is no longer a concern to government ornithologists.

Two buzzards, taking advantage of fence posts on the east side of Mitchell cabin, warm themselves in the morning sun. What to call these birds, by the way, is hotly contested. For some, the only correct name is “vulture.”

The American Heritage Dictionary says a buzzard is “any of various North American vultures, such as the Turkey vulture.” A “chiefly British” meaning for the word buzzard, notes the dictionary, is “a hawk of the genus Buteo, having broad wings and a broad tail.”

The word can also refer to “an avaricious or otherwise unpleasant person,” the dictionary adds. For reasons that seem odd to me, ornithologists around West Marin seem to be chiefly British. Hey, this is Old West Marin, as the sign on the Old Western Saloon affirms. When a cowboy calls a bum “you old buzzard,” he means “you old carrion eater.” He certainly doesn’t mean you old “hawk [with] broad wings and a broad tail.”

A couple of roof rats visit the deck every evening to eat birdseed that the birds overlooked. Adult roof rats are 13 to 18 inches long, including their tails which are longer than their bodies.

They have been known to eat bird eggs, but they, in turn, are eaten by barn owls. As it happens, I saw one family of barn owls nesting at a neighbor’s house last week, so nature may still be in balance hereabouts.

The jackrabbit that this summer began hanging out around the hill sees me on the deck but remains motionless so as not to attract my attention.

A blacktail buck takes a rest next to the front steps a short distance from the deck. Although two of us took turns photographing him, he must have felt safe, for he stuck around.

The buck, in fact, seems fairly comfortable around people. Here he watches my neighbor Mary Huntsman gardening. She was unaware of his presence until I later showed her this photograph.

Almost every evening around 11 p.m., a gray fox shows up at the kitchen door, looking for bread. Lynn and I typically spend half an hour feeding him cheap, white bread one slice at a time.

Then he’ll disappear in search of more substantial fare. How do I know this? He leaves his seed-filled scat in prominent places around the property. The fox obviously has great balance, for he even leaves deposits on top of fence posts. I don’t know whether to be disgusted or impressed.

Outside our kitchen, an appropriately named “wake” of eight buzzards (aka vultures) takes a rest while on a search for corpses.

Outside our kitchen, an appropriately named “wake” of eight buzzards (aka vultures) takes a rest while on a search for corpses. Two quail watching over nine of their chicks. (Photo by Lynn Axelrod Mitchell)

Two quail watching over nine of their chicks. (Photo by Lynn Axelrod Mitchell)