Because the bottomlands of Drakes Estero are under the jurisdiction of the State of California, which by law must forever protect them for fishing, including aquaculture, they can never become part of a Wilderness Area of the National Park Service.

This legal fact may in the long run be the main obstacle to the Point Reyes National Seashore administration’s machinations to close Drakes Bay Oyster Company three years from now.

This legal fact may in the long run be the main obstacle to the Point Reyes National Seashore administration’s machinations to close Drakes Bay Oyster Company three years from now.

In an historical and legal analysis posted Wednesday on the Community Conversations page of the Marinwatch website, attorney Sandy Calhoun writes, “When the State of California transferred the submerged lands in Point Reyes National Seashore to the United States in 1965, the State Legislature… retained for the people of California fishing rights on and over submerged lands.”

Nor did the Legislature have the power to transfer those rights to the federal government, even if it had wanted to, although in the last couple of years, the acting director of the State Department of Fish and Game has acted as if he could cede “primary management authority” over the estero to the park. In fact, the acting director also lacks the legal ability to do so, attorney Calhoun writes.

“The California Constitution prohibits the State Legislature from transferring away the public ‘right to fish,’ which includes oyster cultivation,” Calhoun notes, and “what the California Legislature cannot do directly cannot be done indirectly by an administrative interpretation of an act of the State Legislature.

“In short, it would be unconstitutional for the California Department of Fish and Game to administratively cede jurisdiction over oyster cultivation in Drakes Estero [below] to the National Park Service.”

In 1974, when the Park Service wrote an environmental-impact statement for the proposal to designate 10,600 acres of the Point Reyes National Seashore as wilderness, the park noted that “control of the [oyster company] lease from the California Department of Fish and Game, with presumed renewal indefinitely, is within the rights reserved by the state on these submerged lands.”

In 1974, when the Park Service wrote an environmental-impact statement for the proposal to designate 10,600 acres of the Point Reyes National Seashore as wilderness, the park noted that “control of the [oyster company] lease from the California Department of Fish and Game, with presumed renewal indefinitely, is within the rights reserved by the state on these submerged lands.”

When the Sierra Club broke with other environmental groups and complained about the bottomlands not being also designated as wilderness, the Park Service responded, “It has been the policy of the National Park Service not to propose wilderness for lands on which the United States does not own full interests.”

Nor is the state government’s interest in leasing bottomlands to the oyster company merely a matter of regulating operations and collecting fees.

The California Aquaculture Promotion Act of 1995 proclaims: “The Legislature finds and declares that while commercial aquaculture continues to provide considerable benefit to people of the state, the growth of the industry has been impaired in part by duplicate and costly regulations and illegal importation and trading in aquaculture products.

“The Legislature further finds and declares that commercial aquaculture shall be promoted through the clarification of respective government responsibilities and statutory requirements.”

As part of the state’s policy of promoting aquaculture, Drakes Bay Oyster Company is required to meet minimum production goals established by the California Fish and Game Commission. It can lose its lease to use the estero’s bottomlands if it doesn’t.

“These lease provisions, which confirm the state’s compelling interest in preserving and increasing the productivity of shellfish cultivation in Drakes Estero, demonstrate that oyster cultivation under state permits is not a commercial operation in the usual sense,” attorney Calhoun writes.

“Rather, in this context, ‘commercial’ is a shorthand term for private development of a state-retained, approved, and regulated use of a state resource, i.e. the bottomland in Drakes Estero.”

National Seashore Supt. Don Neubacher would like to shut the oyster company down in 2012 when the use permit for its onshore facilities (at right) comes up for renewal, but the onshore facilities are also protected.

National Seashore Supt. Don Neubacher would like to shut the oyster company down in 2012 when the use permit for its onshore facilities (at right) comes up for renewal, but the onshore facilities are also protected.

While the State of California doesn’t own any part of the oyster company’s onshore facilities, Section 16 of the federal Wilderness Act requires the Secretary of the Interior to provide “adequate access” to private or state-owned land within wilderness areas.

In 1997, before the Johnson family sold the oyster company to its present owners, the Lunny family, the park proposed the oyster company’s old buildings be replaced, and Supt. Neubacher himself signed a building permit application to add 3,500 square feet to the facilities.

In the environmental assessment prepared by Neubacher, the park superintendent argued that the new buildings were needed. “Because the aquaculture operation will be allowed to continue,” Neubacher wrote, “the proposed project will preserve aquaculture, specifically oyster processing and harvesting at Drakes Estero.”

Neubacher added that the “project will positively impact the local economy. Johnson Oyster Company accounts for 39 percent of the State of California’s commercial oyster harvest.”

But officialdom is always capricious. Less than a dozen years later, Neubacher and his bosses have changed their minds and now want to destroy the historic oyster company. In the past three years they’ve lined up a Bush-era lawyer for the Park Service, a faceless state bureaucrat, and a handful of environmental zealots to help rationalize the destruction.

Should all this end up in court some day, one key issue will be what Congress intended when it designated Drakes Estero “potential” wilderness back in 1976.

The field representative for Congressman John Burton (at left), who sponsored the legislation in the House of Representatives, was the late Jerry Friedman of Point Reyes Station, chairman of the county planning commission and co-founder of the Environmental Action Committee of West Marin.

The field representative for Congressman John Burton (at left), who sponsored the legislation in the House of Representatives, was the late Jerry Friedman of Point Reyes Station, chairman of the county planning commission and co-founder of the Environmental Action Committee of West Marin.

Writing on behalf of Congressman Burton and half a dozen environmental groups, Friedman told senators holding hearings on the wilderness bill that it was written so as to “allow the continued use and operation of Johnson’s Oyster Company in Drakes Estero.”

Alan Cranston and John Tunney co-sponsored the wilderness legislation in the Senate. In written testimony, Senator Tunney noted that under the bill, “the existing agricultural and aquacultural uses can continue.” Senator Cranston took the same position both orally and in writing, as records of the hearings show, attorney Calhoun writes.

In separate legislation, Congress in 1980 declared that “encouraging aquaculture activities and programs in both the public and private sectors” was federal policy. Like the State of California, Congress complained that jurisdictional questions and misplaced government regulations were interfering with “the potential for significant growth” in US aquaculture.

In short, even if the Park Service decides to unilaterally reinterpret the concept of “potential wilderness,” Congress and the Legislature have already declared that more, not less, aquaculture is needed. Supt. Neubacher may want to defy Congress, the Legislature, and the state constitution, but it’s doubtful that any court will let him.

Most West Marin residents want the oyster company to survive, and because the State of California has an established interest in promoting aquaculture in the estero, it’s time for Assemblyman Jared Huffman and State Senator Mark Leno to join US Senator Dianne Feinstein in coming to the aid of Drakes Bay Oyster Company.

And if you have the time, attorney Sandy Calhoun’s 28-page analysis of all this is a good read. Its file can be found under “Drakes Estero: Historical Analysis of Oyster Cultivation and Wilderness Status by Alexander D. Calhoun” on Marinwatch’s Community Conversations page (near the bottom).

I’ve see badgers for sale as food in a Guangzhou, China, marketplace. And badgers were once a staple of the Native American, as well as colonial, diet. Even today they’re commonly eaten in France, Russia, and other European countries, as well as China.

I’ve see badgers for sale as food in a Guangzhou, China, marketplace. And badgers were once a staple of the Native American, as well as colonial, diet. Even today they’re commonly eaten in France, Russia, and other European countries, as well as China.

In 2007, Marin County supervisors asked Senator Dianne Feinstein (right) to intervene after the Point Reyes National Seashore administration began harassing the oyster company.

In 2007, Marin County supervisors asked Senator Dianne Feinstein (right) to intervene after the Point Reyes National Seashore administration began harassing the oyster company. The conflict began with an

The conflict began with an  The first exposure occurred in July 2008 when the Inspector General’s Office of the Interior Department issued a

The first exposure occurred in July 2008 when the Inspector General’s Office of the Interior Department issued a  “That really is a policy and law issue,” said Jarvis (right), “not a science issue.”

“That really is a policy and law issue,” said Jarvis (right), “not a science issue.” This legal fact may in the long run be the main obstacle to the Point Reyes National Seashore administration’s machinations to close Drakes Bay Oyster Company three years from now.

This legal fact may in the long run be the main obstacle to the Point Reyes National Seashore administration’s machinations to close Drakes Bay Oyster Company three years from now. In 1974, when the Park Service wrote an environmental-impact statement for the proposal to designate 10,600 acres of the Point Reyes National Seashore as wilderness, the park noted that “control of the [oyster company] lease from the California Department of Fish and Game, with presumed renewal indefinitely, is within the rights reserved by the state on these submerged lands.”

In 1974, when the Park Service wrote an environmental-impact statement for the proposal to designate 10,600 acres of the Point Reyes National Seashore as wilderness, the park noted that “control of the [oyster company] lease from the California Department of Fish and Game, with presumed renewal indefinitely, is within the rights reserved by the state on these submerged lands.” National Seashore Supt. Don Neubacher would like to shut the oyster company down in 2012 when the use permit for its onshore facilities (at right) comes up for renewal, but the onshore facilities are also protected.

National Seashore Supt. Don Neubacher would like to shut the oyster company down in 2012 when the use permit for its onshore facilities (at right) comes up for renewal, but the onshore facilities are also protected. The field representative for Congressman John Burton (at left), who sponsored the legislation in the House of Representatives, was the late Jerry Friedman of Point Reyes Station, chairman of the county planning commission and co-founder of the Environmental Action Committee of West Marin.

The field representative for Congressman John Burton (at left), who sponsored the legislation in the House of Representatives, was the late Jerry Friedman of Point Reyes Station, chairman of the county planning commission and co-founder of the Environmental Action Committee of West Marin.

Ratty, as he is called in The Wind in the Willows, showed up on my deck Tuesday to take a drink from the birdbath and eat whatever birdseed he could find.

Ratty, as he is called in The Wind in the Willows, showed up on my deck Tuesday to take a drink from the birdbath and eat whatever birdseed he could find.

In Spring a young raccoon’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love, to paraphrase Tennyson.

In Spring a young raccoon’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love, to paraphrase Tennyson. Even more of a surprise was that they sometimes appeared to be actually making love.

Even more of a surprise was that they sometimes appeared to be actually making love. Windstorm destruction. The historic house where Dave Dinsmore lives on Nicasio Square has withstood more than a couple of blows over the years from speeding southbound vehicles. Coming at the end of a long straightaway into town, Nicasio Valley Road’s 90-degree turn in front of the house has sent nighttime speeders flying off the road and into the fence and porch. This week, however, the blow came from a gale that sent half a tree crashing down onto the porch’s roof. No doubt the resilient residence will recover from this blow too.

Windstorm destruction. The historic house where Dave Dinsmore lives on Nicasio Square has withstood more than a couple of blows over the years from speeding southbound vehicles. Coming at the end of a long straightaway into town, Nicasio Valley Road’s 90-degree turn in front of the house has sent nighttime speeders flying off the road and into the fence and porch. This week, however, the blow came from a gale that sent half a tree crashing down onto the porch’s roof. No doubt the resilient residence will recover from this blow too.

Reflected in the windows of neighbors Dan and Mary Huntsmans’ potting shed, a cat that could never have perched on their gatepost in this week’s gale could sit there nonchalantly last week.

Reflected in the windows of neighbors Dan and Mary Huntsmans’ potting shed, a cat that could never have perched on their gatepost in this week’s gale could sit there nonchalantly last week.

Here’s a poke at the kind of personal ads that show up locally in The Bay Guardian or on Craigslist.

Here’s a poke at the kind of personal ads that show up locally in The Bay Guardian or on Craigslist.

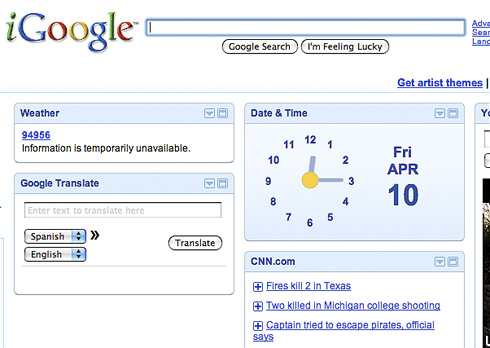

Just to see if the goofy temperature Google had listed around noon Tuesday was merely a brief aberration, I checked again at 2:22 a.m. Wednesday. By now the air outside had warmed up some, according to Google, but our springtime night was still 12 degrees below freezing. Meanwhile, my own outdoor thermometer showed an air temperature of just over 50 degrees.

Just to see if the goofy temperature Google had listed around noon Tuesday was merely a brief aberration, I checked again at 2:22 a.m. Wednesday. By now the air outside had warmed up some, according to Google, but our springtime night was still 12 degrees below freezing. Meanwhile, my own outdoor thermometer showed an air temperature of just over 50 degrees. By 2 p.m. Wednesday, my thermometer indicated the air outdoors had risen to 60 degrees, so I checked what Google was reporting and this time found Point Reyes Station sounding like a town in the tropics. If I were to believe Google, the temperature here had soared by 113 degrees in 26 hours. What is going on?

By 2 p.m. Wednesday, my thermometer indicated the air outdoors had risen to 60 degrees, so I checked what Google was reporting and this time found Point Reyes Station sounding like a town in the tropics. If I were to believe Google, the temperature here had soared by 113 degrees in 26 hours. What is going on? Addendum: By Friday, Google was reporting that in Point Reyes Station’s zip code, current temperature “information is temporarily unavailable.” I’d like to think that this blog had something to do with that, but I doubt it.

Addendum: By Friday, Google was reporting that in Point Reyes Station’s zip code, current temperature “information is temporarily unavailable.” I’d like to think that this blog had something to do with that, but I doubt it.

Closely following Friday’s discussion are oyster company owners Kevin and Nancy Lunny.

Closely following Friday’s discussion are oyster company owners Kevin and Nancy Lunny.

The “most common industries for males” working in West Marin, City-Data.com says, are: “construction, 17 percent; professional, scientific, and technical services, 10 percent; agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, 10 percent; educational services, 8 percent; accommodation and food services, 7 percent; health care, 5 percent; arts, entertainment, and recreation, 5 percent.”

The “most common industries for males” working in West Marin, City-Data.com says, are: “construction, 17 percent; professional, scientific, and technical services, 10 percent; agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, 10 percent; educational services, 8 percent; accommodation and food services, 7 percent; health care, 5 percent; arts, entertainment, and recreation, 5 percent.” The Miwok Indian cemetery at Reynolds (where Tony’s Seafood is located; the restaurant’s white buildings can be seen in the background) From 1875 to 1930, Reynolds was a whistlestop on the narrow-gauge railroad, and numerous Miwoks lived nearby. A few of their descendants still do. The cemetery belongs to the Miwok Rancheria in Graton, Sonoma County.

The Miwok Indian cemetery at Reynolds (where Tony’s Seafood is located; the restaurant’s white buildings can be seen in the background) From 1875 to 1930, Reynolds was a whistlestop on the narrow-gauge railroad, and numerous Miwoks lived nearby. A few of their descendants still do. The cemetery belongs to the Miwok Rancheria in Graton, Sonoma County. Today, of course, is the first day of Spring, and wildflowers have begun blooming around the plastic flowers that decorate each cross.

Today, of course, is the first day of Spring, and wildflowers have begun blooming around the plastic flowers that decorate each cross.

“The heart of the group’s activity, listed cryptically on its Web site’s calendar as ‘morning practice,’ is closed to all but the residents. At 7 a.m. each day,” The Times reports, “about a dozen women, naked from the waist down, lie with eyes closed in a velvet-curtained room, while clothed men huddle over them, stroking them in a ritual known as orgasmic meditation,” ‘OMing,’ for short.

“The heart of the group’s activity, listed cryptically on its Web site’s calendar as ‘morning practice,’ is closed to all but the residents. At 7 a.m. each day,” The Times reports, “about a dozen women, naked from the waist down, lie with eyes closed in a velvet-curtained room, while clothed men huddle over them, stroking them in a ritual known as orgasmic meditation,” ‘OMing,’ for short.

A warning sign of Spring: Hundreds of people showed up at the Dance Palace this afternoon for Sacred Heart Church’s annual St. Patrick’s Day Barbecue.

A warning sign of Spring: Hundreds of people showed up at the Dance Palace this afternoon for Sacred Heart Church’s annual St. Patrick’s Day Barbecue.

A volunteer bartender at the St. Patrick’s Day Barbecue, Mark Allen (left) of Inverness Park, takes an order for an Irish coffee.

A volunteer bartender at the St. Patrick’s Day Barbecue, Mark Allen (left) of Inverness Park, takes an order for an Irish coffee.

Another warning sign of Spring: The gloomy days of winter are supposed to be over “when the red, red robin comes bob, bob, bobin’ along.” But at Jay’s home this year, the first robin of Spring is not “red, red” but partially albino. (Photo by Jay Haas)

Another warning sign of Spring: The gloomy days of winter are supposed to be over “when the red, red robin comes bob, bob, bobin’ along.” But at Jay’s home this year, the first robin of Spring is not “red, red” but partially albino. (Photo by Jay Haas)