Sun 23 Oct 2011

Occupy Wall Street protest expands to Point Reyes Station

Posted by DavidMitchell under General News, Point Reyes Station

Comments Off on Occupy Wall Street protest expands to Point Reyes Station

Approximately 65 people showed up Sunday morning in West Marin School’s parking lot to take part in the Occupy Wall Street movement, which began Sept. 17 in New York City and since then has spread around the world.

As of two weeks ago, there had been protests in 70 major US cities and more than 600 smaller communities. There had also been protests in more than 900 foreign cities. A Time magazine survey earlier this month found that 54 percent of Americans have a favorable impression of Occupy Wall Street while 18 percent do not.

The movement is in essence a protest against the unequal distribution of wealth in the United States and elsewhere. In this country, the protesters’ slogan “We are the 99 percent” refers to the disparity in wealth between the top one percent of society and other citizens.

The phrase came out of the 2000 presidential candidate debates between Al Gore and George W. Bush. Gore repeatedly accused Bush of supporting the “wealthiest one percent” rather than the welfare of everyone else. That was followed by a 2006 documentary film, The One Percent, made by Johnson & Johnson heir Jamie Johnson. The film noted that the wealthiest one percent of Americans then controlled 38 percent of the nation’s wealth.

Already this country’s disparity in wealth was well known. In 2001, Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel winner in economics, had written that the wealthiest one percent of US citizens at that time controlled 40 percent of America’s wealth.

Among those assembling to be photographed at West Marin School was Congressional candidate Norman Solomon (in blue shirt). Sunday’s protest lasted less than half an hour and caused no disruptions.

Among those assembling to be photographed at West Marin School was Congressional candidate Norman Solomon (in blue shirt). Sunday’s protest lasted less than half an hour and caused no disruptions.

Because Occupy Wall Street has no list of specific demands — only that income should be spread more evenly and that large corporations should have less influence over government policies — some politicians and mainstream media have dismissed it as irrelevant.

House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-Va) characterized the movement as “growing mobs” and said President Barack Obama’s “failed policies” have pitted “Americans against Americans,” leading to the protests. White House press secretary Jay Carney then accused Cantor of “hypocrisy” since Cantor has been supporting Tea Party protests. “I can’t understand how one man’s mob is another man’s democracy,” Carney said.

The protests are coming at a time when millions of Americans have lost their homes and many millions more have lost their jobs largely because of big banks’ risky lending, which triggered a stock-market crash that has led to a recession.

Many congressional Democrats, including House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, have said they support Occupy Wall Street. In contrast, several high-profile Republicans have denounced it. Presidential candidate Herman Cain, a former banker and pizza chain owner, called the protests “anti-capitalist…. Don’t blame Wall Street, don’t blame the big banks if you don’t have a job and you’re not rich,” he said. “Blame yourself!”

Candidate Ron Paul, however, shot back, “The system has been biased against the middle class and the poor…the people losing jobs. It wasn’t their fault that we’ve followed a deeply flawed economic system.”

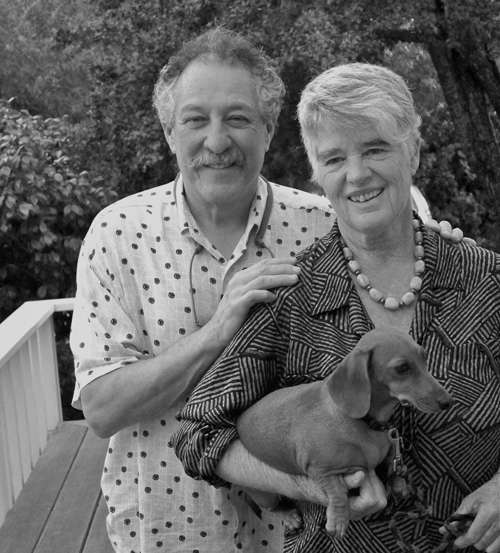

Point Reyes Station photographer Art Rogers, who currently has an exhibition at the Jack Mason Museum of West Marin History, documented the event. Here he directs protesters to find spots where his camera can record everyone’s face.

Giving support to the protests have been a number of labor unions and even several well-off people whose wealth puts them in the upper one percent. Leah Hunt-Hendrix, 28, granddaughter of the conservative, Texas oil tycoon H.L. Hunt, earlier joined Occupy Wall Street protesters and said, “We should acknowledge our privilege and claim the responsibilities that come with it.â€

Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke observed: “People are quite unhappy with the state of the economy and what’s happening. They blame, with some justification, the problems in the financial sector for getting us into this mess, and they’re dissatisfied with the policy response here in Washington. And at some level, I can’t blame them.”

Bank of Canada governor Mark Carney was more emphatic, saying income inequality and economic performance are the main motivators for the protests, which he called “entirely constructive.”

As it happens, Occupy Wall Street is the brainchild of Canada’s Adbusters Media Foundation, which publishes an advertisement-free, anti-consumerist magazine Adbusters. The foundation last summer proposed a peaceful occupation of Wall Street to protest corporate influence on democracy. By now Canada itself has had protests in all 10 of its provinces.

In this country, Vikram Pandit, head of Citigroup, has called the protesters’ sentiments “completely understandable” and said Wall Street has broken the trust of its clients.

Conservative Republicans have called the protests “class warfare,” but Bill Gross, manager of PIMCO’s Total Return Fund, the world’s largest mutual fund, disagreed. “Class warfare by the 99 percent?” he asked. “Of course, they’re fighting back after 30 years of being shot at.” PIMCO’s co-CEO Mohamed El-Erian concurred that people should “listen to Occupy Wall Street.”

Bloomberg news service on Oct. 12 reported, “Hedge-fund manager John Paulson, who became a billionaire by betting against the US housing market and then profited from the recovery of banks, criticized the movement. His townhouse was among those targeted by marchers who left a fake tax-refund check made out for $5 billion on his doorstep, which was barricaded by police.

“’Paulson & Co. and its employees have paid hundreds of millions in New York City and New York State taxes in recent years and have created over 100 high paying jobs in New York City since its formation [in 1994],’ the $30 billion hedge fund said yesterday in a statement. ‘Instead of vilifying our most successful businesses, we should be supporting them and encouraging them to remain in New York City and continue to grow.’â€

Regardless of New York tax rates, the Occupy Wall Street movement by Sunday had spread 2,580 miles from that metropolis on the East Coast to this small town on the West Coast.

Only in Point Reyes Station, there was no Zuccotti Park where sometimes-animated protesters have been camping out near Wall Street. Here there was just a brief get-together in the parking lot of West Marin School where 65 residents stood absolutely still to be photographed protesting.