When the great storm of 1982 struck West Marin, particularly the Inverness area, on Jan. 3 and 4, nobody in town died although 33 people elsewhere around the San Francisco Bay area were killed, mostly by landslides.

A major slide closed Highway 101 in the Sausalito area while a smaller, but still significant, slide closed Sir Francis Drake Boulevard between Inverness and Inverness Park. As it happened, there were no sheriff’s deputies or highway patrol officers west of the slide when it occurred, so, in the words of the late sheriff’s lieutenant Art Disterheft, the Inverness Volunteer Fire Department became “the only law west of the Pecos.”

Firefighters requisitioned food from the Inverness Store and distributed it to people without their own supplies while St. Columba’s Episcopal Church fed others. People lost homes, and dairy ranchers had to dump thousands of gallons of milk which they couldn’t haul to the creamery in Petaluma before the milk spoiled.

Among those who lost their homes were John Robbins, who built most of West Marin’s cable TV system, and his former wife Barbara Lakshmi Kahn, a visionary artist. Their home was next to Redwood Creek just uphill from the juncture of Papermill Creek and Tomales Bay.

For this 30th anniversary of the disaster, John wrote an account of what it was like to go through it.

By John Robbins

It began with my getting ready to head up to Rocklin, east of Sacramento. I was doing cable TV design work up there, pending the start of construction of the system in West Marin. The rain was coming down steadily, but I had no sense of alarm. The stream was flowing pretty much at capacity coming out of the culvert on the downhill side of our driveway.

Other than that, everything appeared normal. I had slept well through the night and had no idea how intense and continuous the rain had been falling. Kris [John’s stepson] had already left for Drake High, hitching a ride with our neighbor Chuck Wallace, who worked at Chevron in Richmond.

A few minutes later they returned, being unable to navigate Sir Francis Drake Boulevard because of landslides further east toward Inverness Park. Chuck came in the house to share a cup of tea around the toasty woodstove, but he didn’t stay long, wanting to get on up to his house. My first thought upon seeing their return was that I couldn’t leave town. What a pleasant thought!

But that thought didn’t last very long. After Chuck had been gone a few minutes, I looked out the window at the culvert under our driveway. The flow had been reduced by at least half. Immediately, I realized something must be blocking the upper end of the pipe (16 inches in diameter). I grabbed a shovel and went up to see what I could do. NOTHING.

No branches were blocking the opening. When I stuck the shovel down, it sunk into pure decomposed granite, which by this time had completely blocked the entrance. Water was rapidly filling the culvert and beginning to overflow the driveway.

Fortunately, as I made my way back to the house, our two cars were sitting in the driveway, allowing me to brace myself against the rush of the water now roaring down a new channel before returning to the normal creek bed, further down hill beyond the driveway. If the cars had not been there I would have never made back to the house. As it was, it was pretty dicey.

Back at the house again, my thoughts went to reducing the chance of flooding indoors. I grabbed a piece of plywood and nailed it across the bottom 16 to 18 inches of the doorway, thinking that this would at least divert any flow that might get that high. Kris was standing out on the front porch observing what I was doing.

I was inside the doorway, looking up the canyon at a thicket of bay shoots and alders 100 feet at most up the creek. At that very moment, a wall of brown broke through the trees. It had a form, not unlike a 3-foot to 4-foot wave cresting to break out at the beach. It is amazing the amount of detail one can remember in but an instant.

I grabbed Kris by his lapels and pulled him over the plywood, into the house, then slammed the door and braced myself against it, not really thinking about the mass moving towards us. The door faced toward the creek, so the coming wave would be a sideways blow to the door.

A few feet from the doorway was a large plate glass window, maybe 4 feet by 6 feet, through which Kris had a great view. He called out, “There go the cars.” Then the bottom half of the door bent open like a piece of paper being peeled back in one corner. A rush of mud, maybe a couple of wheel barrows’ worth and about the consistency of concrete being poured, slopped in through the opening.

There were loud scraping, creaking sounds and shaking walls. As I held the door, awaiting the impact, I hoped that the posts of an overhead covering, which I had recently built on the upstream face of the house, would help to cushion the blow.

The rush of mud subsided, and a large tangle of bay trunks and branches came to a stop with one ragged, stumpy end just breaking through the glass and coming to a rest less than a foot into the room in the upper part of the window frame.

Both cars had been swept, side by side, into the creek. A bit of the roof of Barbara’s powder-blue VW bug was barely visible beneath my ocher-colored Datsun, along with a jumble of foliage, mud, and rock. All those skinned tree trunks exuded a very pungent ester of bay, a smell that to this day I do not favor.

It is amazing that the upstream wall didn’t collapse. Perhaps the fireplace and chimney structure gave it the strength needed not to crumble at that moment. Whatever it was, the house had withstood the blow. Barbara, Kris, and I gathered together and embraced and gave thanks for our safe passage through this event. But not for long.

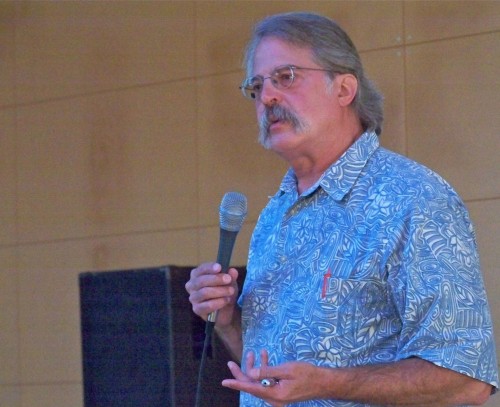

Aum is the Heart of My Home, a 1977 visionary painting by Barbara Lakshmi Kahn. The Aum symbol, which is also written as Om, is sacred in several Eastern religions.

The fire in the stove was going full blast. There was mud at the front door, which was completely blocked by the knot of trees that had broken the window. I dampened the fire while Barbara headed into her studio to start putting art work up into the loft. I joined her to help with the art materials. I was passing paintings up to her as she stood halfway up the ladder.

She paused, not taking the piece I was holding, and instinctively said, “I just got a message that we must leave, NOW!” I agreed. Meanwhile, Kris had been in his room, putting a few things in his backpack, a pair of undershorts, some socks, making ready to leave.

The only door was blocked, meaning we would have to go out the living room window. It was now flooded on the side of the house away from the creek, with about a foot or so of muck out there.

To get out the window we would have to step onto the arm of the sofa, the sofa we had just purchased. It was a great little couch with a fairly comfortable pull-out bed. My comment, back to Barbara and Kris, as I was about to jump out into the muck, was, “Careful how you step on the couch. We don’t want to get the cushions dirty.”

It hadn’t really registered just how dangerous our situation was. I was thinking, in some vague way, that the surge we had just gone through had relieved all the pressure upstream. In a way, I was on automatic drive. Just doing what needed to be done in the moment.

Once we were all outside, we gingerly made our way across the yard to near the base of the hill to our south. It was steep and thick with the usual foliage, but it was our only route for escape. The yard was filled with muck almost up to our knees.

At the base of the hill there was a very strong flow of water, now diverted far from the normal stream bed, which was on the other side of the house next to the road. Fortunately, a bay sapling had come down in the debris flow, and it formed something of a bridge to enable us to ford the new stream.

I warned Barbara not to step ahead of me, but it was too late. Step she did and immediately went down as her feet slipped out from under her. I was able to get my thumb and one finger gripped on her shoulder, just enough to keep her from being swept away, and this made it possible for me to get her back on her feet.

I then waded out into the new stream, keeping a firm grip on the sapling. This allowed me to swing Barbara and then Kris across the torrent safely to the other side. We then made our way up the side of the hill, pulling ourselves up through the ferns and wild berry bushes to Peter and Marcia Fox’s house. They weren’t home.

We then went down their driveway to Doreen Powell’s house, which looked right out over Sir Francis Drake Boulevard and Redwood Avenue. Doreen and Biff were home and managed to find us some dry clothes to change into.

Right after we had changed clothes, we heard an ominous rumble, something like rolling thunder, that just kept getting louder each moment. I looked out the window and saw the electric lines feeding up our canyon dancing wildly in the air. The one utility pole I could see on Sir Francis Drake Boulevard was swaying back and forth and then snapped abruptly toward the bay.

John, Barbara, and Kris’ home was on Redwood Avenue (at bottom of map) beside Redwood Creek. At the upper left-hand corner is Motel Inverness.

My gaze shifted downward below the lines just in time to see an entire chunk of wall, with the plate glass window frame and one of Barbara’s large paintings still hanging on it, rumbling across Sir Francis Drake Boulevard at about 20 mph. It was like a raft going down the rapids of the Colorado River.

It was at that point I uttered, “I don’t know why this has happened to us, but I know it is for our own good.” It was the only thing I could think to say. It just came out with no thought beforehand.

Not long after witnessing that awful scene, we made our way down the street to look in disbelief at a huge chunk of our roof wedged up under some willow trees with our TV sitting on the roof amid the branches. (Months later, after letting it dry out thoroughly, I plugged it in and found that it actually worked. It eventually became the TV set that I used to tune the cable-system signals at the head-end site.)

It was all like a dream for awhile, a very lucid dream. When Bob Gillespie saw us on the road as he approached from the Inverness side of the flow that was coming down Redwood Canyon, I think we were all numb. We had no idea what to do next other than to stare in disbelief, but there it was before our eyes, not a dream, unless this is ALL a dream. (Which, of course, it probably is.)

It certainly was a pretty clean sweep. Nothing showed that there had ever been a house on our property except for one pipe sticking out of the ground.

When I searched through the debris spread along the marsh beside Tomales Bay during the ensuing days, I found that everything had remained in relative position to other items. They were arrayed in an elongated fashion as if spread like a deck of cards across the table.

It became possible to then search for items and have some success. I may have spent the next six weeks or more pawing through that mess, finding treasures here and there. It was very therapeutic, sadness with the losses but great joy on discovery of some undamaged piece of the past.