Wed 27 Feb 2019

Caveat lectorem: When readers submit comments, they are asked if they want to receive an email alert with a link to new postings on this blog. A number of people have said they do. Thank you. The link is created the moment a posting goes online. Readers who find their way here through that link can see an updated version by simply clicking on the headline above the posting.

For Valentine’s Day my wife Lynn gave me a book with an intriguing title. It’s Lust on Trial by Amy Werbel (Columbia University Press, 2018).

Dr. Werbel is associate professor of the history of art at New York State University’s Fashion Institute of Technology. Her book explains how 40 years of misguided attempts to maintain New England Calvinism as America’s culture made it possible for almost any works showing a naked body, from fine art, to erotica, to medical texts, to be prosecuted as obscene. Unfortunately, some laws shaped by that era still haunt parts of our country today.

Professor Amy Werbel

At the center of her account is a Puritanical, anti-vice crusader from New Canaan, Connecticut, Anthony Comstock (1844-1915). He for 40 years wielded so much clout that the 1873 federal anti-obscenity law was named the Comstock Act.

Comstock helped found the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Working with police in the state, the NYSSV seized tons of supposed obscenities, which even included pictures from Paris that were regarded as fine art in France.

“The leaders of the NYSSV all presumed the existence of a ‘racio-cultural hierarchy,’ with ‘Teutonic/Anglo Saxons at the top,'” Werbel writes. “Given their belief that Anglo-Americans already possessed the greatest culture on earth, it seemed natural to view French influences generally as a form of pollution.”

French Catholicism, in NYSSV eyes, failed to condemn all public exhibition of nude art whereas American Protestantism recognized a social need for enforcing Calvinistic standards of morality.

Â

Â

Anthony Comstock in his New York office around 1900. (All photos in posting from ‘Lust on Trial’)

For 40 years as an inspector in the post office department, Comstock “vigorously asserted his power to serve as a Christian censor of morals within a supposedly secular government position,” Werbel writes. Among the “obscenities” Comstock also sought to suppress as supposed threats to morality were condoms, dildos, and birth-control information. He also fought in court to prohibit abortion. Ironically, his opposition to birth control and abortion was largely to insure that couples indulging in illicit sex would pay the penalty of having a baby.

‘Nymphs and Satyr’ by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 1873.

In Bouguereau’s “playful” painting, Werbel explains, “the satyr had been caught spying on a group of nymphs who are now taking their vengeance by dragging him into a nearby pond. Satyrs can’t swim, and so his lust has been swiftly transferred into mortal terror.”

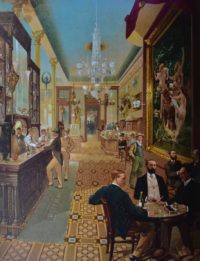

The Grand Saloon in the Hoffman House.

Although photos of the painting were ruled obscene in New York in 1883, they continued to circulate. The original painting of Nymphs and Satyr, meanwhile, hung on the wall of “the Grand Saloon” in the Hoffman House Hotel. The large painting had remained in place despite Comstock telling the hotel’s owner in 1885 to remove it. This was an expensive establishment geared to the wealthy upper class, and Comstock would soon learn that such people could not be successfully prosecuted.

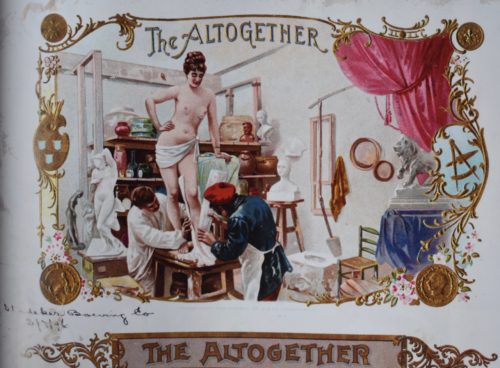

An 1896 cigar label was considered an example of yet another medium being used for disseminating “obscenity.”

Comstock’s primary goal in suppressing all erotic images seems odd today. In his mind, the greatest danger they posed was to inspire lust which, in the case of boys, could lead to masturbation, and he considered self-gratification the worst of sins. We know his thoughts on this because Comstock at the age of 19 made an apparent reference in his diary to masturbating: “I debased myself in my own eyes today by my own weakness and sinfulness, was strongly tempted today, and oh! I yielded…. What suffering I have undergone since, no one knows.”

A year later having joined Connecticut’s Company H in the Union Army, Comstock saw the pornography that other soldiers had ordered through the mail, and he “again recorded giving into the same vices that plagued him in New Canaan.” His diary, two other biographers have noted, was “filled with confessions of guilt and outbursts of bitter remorse during these years.” Nor did “Comstock’s obsession with lust and masturbation” ever change, the book notes.

In the case of girls, as he saw it, the main danger of any lust resulting from obscenities was not that it would lead to masturbation but that it tended to make the girls indecent. When a short-lived American Student of Art magazine published nude pictures of both men and women, Comstock put it on trial for influencing girls to “turn to lives of shame,” insinuating that the arousal of girls “might lead them to prostitution.”

Although Comstock seized hundreds of dildos, they confused him. He believed respectable women were “passionless” and that for any female, arousal depended on “male impetus.” When his investigations turned up a dildo which was somewhat expensive by standards of the times, he wondered who the customers were? “Prostitutes don’t use them,” he reasoned. “The married do not. Their cost being about $6 would seem to preclude their use by the poor and the low.” Werbel writes that Comstock was “entirely unable to fathom that an unmarried woman of means might want to take pleasure from masturbation using an artificial penis.”

Ironically, as the author notes, “one of the most common diseases serious doctors diagnosed among women in the mid-nineteenth century was ‘female hysteria’…. Many recommended curing the problem with induced orgasms, either produced by physicians who massaged the vulva by hand, often on a weekly basis, or hydrotherapy that directed a strong stream of water onto the clitoris.” This was time-consuming, Werbel adds, and ultimately led to doctors inventing the electric vibrator.

Figure in Motion by Robert Henri.

Since the reason displays of nude bodies were obscene, as Comstock saw it, was that they inspired lust, arousal was his personal test for obscenity; if something turned him on, it was obscene. When it came time for his defendants to go on trial, juries for their own protection were for years not allowed to see the “vile” evidence that had been seized, and even when defendants were acquitted, they often didn’t get their goods back.

By 1900, however, Comstock’s judgment was being increasingly challenged. After he led a string of raids on “vendors of improper photographs” in Philadelphia in 1886, the vendors argued in court that the photos were high art or were pictures to be used by artists who couldn’t afford a live model.

Even though Comstock argued that the New York Court of Errors and Appeals had found the same pictures to be obscene, the Philadelphia judge quickly threw out the cases. “It seems absurd for New York detectives to come over here and try to demonstrate that recognized works of art are obscene,” he remarked.

When the American Society of Artists publicly protested seizures of art, it declared, “We believe that the study of the nude in art is not only innocent, but is refining and ennobling.”

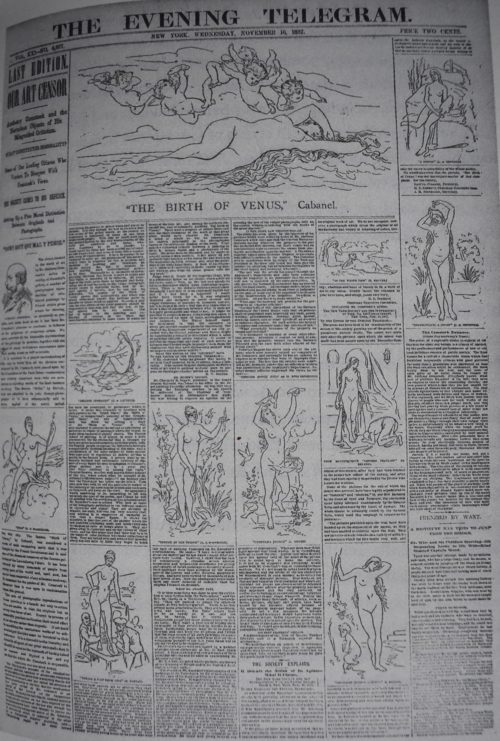

After Comstock seized art from the Knoedler gallery in New York, The Evening Telegram responded by printing on Page 1 the pictures that he didn’t want the public to see. Comstock then tried to get the district attorney to indict The Telegram but was abruptly turned down.

Other newspapers were also beginning to mock Comstock’s censorship. Commenting on all this, The New York Times wrote that Comstock exemplified “persons of a low grade of intelligence and a prurient turn of mind.” The Springfield Republican called him “the most preposterous ass that walks on two legs.”

‘Anthony Comstock: The Village Nuisance’ by Louis Glackens was published as a cartoon in a humor magazine called Puck. “While he holds up his hands in protest, Comstock at the same time fixes his gaze firmly at his enticement,” Werbel points out. “The scene is a clear reference to his ineffective campaign to rid shop windows of such suggestive displays.

“At the upper left, Comstock leads clothed horses down a park path, and below that he attempts to serve a warrant on ‘a shameless French poodle.’ On the right… we see Comstock bathing fully clothed and, finally, in the last scene he ‘gets what is coming to him,’ tormented by winged devils in the fiery abyss of hell, in which he wears only a peek-a-boo carnival mask across his ample posterior.”

In his prosecutions, Comstock typically cited England’s Hicklin test for obscenity. If something erotic could disturb even the most vulnerable people, such as small children, it was considered obscene. Not until 1957 did the U.S. Supreme Court finally stop the use of the Hicklin test for determining obscenity. From now on, it ruled, Congress could ban only material “utterly without redeeming social importance.” What mattered was “whether to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to the prurient interest.”

It seems significant that when Comstock died in 1915, there was far more sexual material in the country than when he began his anti-vice campaign. Indeed, he “had helped to make figure painters, sculptors, and nude models extremely sexy,” the author observes. Moreover, his prosecutions frequently proved to be valuable publicity for whatever was on trial.

By our standards, some of Comstock’s own standards would be considered immoral. For example, “he viewed child sex trafficking as largely the fault of the victims,” according to the author. He “placed the blame for ‘White Slavers’ squarely on the girls who had ‘already been dragged down to perdition by the perverted imagination.'”

Over several weeks in 1899 alone, a series of girls, who were caught in the nets of traffickers, out of desperation committed suicide (using poison) in one particular tavern, McGurk’s saloon in the Bowery. “Comstock,” the book says, “ascribed their deaths to ‘reading light novels.'”

Werbel quotes Christine Stansell, who also writes about art, as saying one of Comstock’s great unintended accomplishments was to make the opposition coalesce: “The battle to protect free speech linked artists, writers, and professionals of  progressive bent to working-class militants.” These factions Werbel adds, “disagreed on many subjects, but they all wanted the opportunity to be heard, to be read.

“In the following decades, that right waxed and waned both in law and custom, but it has never again been as diminished as during the reign of Anthony Comstock.”

Fascinating history lesson, Dave. Very well-written as always. Amazing that they continued using that Hicklin Test until 1957. I love some of the old-style newspaper phrasing: “The most preposterous ass that walks on two legs.” Indeed.